For the Warwickshire Yeomanry the war in Palestine was over. With the successful defeat of the Ottoman forces in Palestine the War office decided in the spring of 1918 that yeomanry and cavalry units could be retrained as much needed Machine gunners and sent to the Western Front.

Not long after Lieutenant Colonel Gray-Cheape, the regiment’s Commanding officer returned from leave in England, a telegram arrived from the War Office arrived confirming that the Warwickshires were to be amalgamated with the South Nottinghamshire Hussars into the Warwickshire and South Nottinghamshire yeomanry battalion of the Machine Gun Corps.

There were mixed feelings about the merger with cavalrymen excited about the new challenge on the French soil but disappointment that they would not be there to see the end of the Turkish foe they had fought so hard against. Several senior officers, including General Allenby, addressed the Warwickshires before they left for training and General Hodgson said to his adjutant, Lieutenant Armstrong (also of the Warwickshires) that:

I shall always have a soft corner in my heart for the Warwicks, and I hope to hear news of their days in France

Captain F. A. Drake the Warwickshire's Ship's adjutant

The new Battalion was reorganised with Lt-Colonel Gray-Cheape as the senior officer with Major Warwick of the Nottinghamshires as second in command. The two units merged with the first two companies being made up of Warwickshires and the last two of Nottinghamshires commanded by their own officers.

Training began at Victoria Camp on the 10th April for the Nottinghamshires and they were joined three days later by the Warwickshires. They were issued with a maxim machine gun to each company and an NCO instructor but the men were also drilled in Infantry, Gas and bayonet drill, all of which would be invaluable on the Western front during the current German offensive. NCOs and Officers were sent on special training courses at Zeitun. Training went exceptionally well and a live fire demonstration was carried out on the 16th May attended by senior brass.

With the Battalion up to establishment of 54 Officers and 984 other ranks and training complete the Battalion was ordered to Alexandria to be entrained on the 22nd May for its journey to France and on the 23rd May the Battalion joined the Berkshire and Buckinghamshire yeomanry Machine gun Battalion aboard HMT Leasowe Castle. Lt-Col Gray-Cheape took command of all of the soldiers aboard with Captain Drake of the Warwickshires as Ship’s adjutant.

The Leasowe Castle was a Union Castle Mail steamship that had only been completed in 1915 at the Cammell Laird and co. shipyards at Birkenhead. She was originally built for a Greek owner as the Vasiliss Sophia but was requisitioned by the British Government for troop transport duties. As part of the modifications as a troopship she was fitted with eight decks for soldiers, forty two lifeboats and issued with 6” guns and 7.5 Howitzers which were used for defensive fire against U-boats and firing shells at incoming torpedos to divert their course.

On the 20 April 1917 she was damaged whilst sailing ninety miles off Gibraltar by Kapitanleutnant Lothar von Arnauld dela Perière's U-35. Although the damage was substantial there were no casualties and she was able to limp to port for repairs. Fully repaired the Leasowe Castle had had a quiet career and her journey to Marseille to transport the new Machine gun battalion to the Western Front looked to be another easy run.

On the 26th May, at 3 p.m. the vessel joined a convoy of five other vessels in line astern as they passed down the swept channel to the open sea before forming up into a T formation with Leasowe Castle in the third spot. In all the convoy was carrying a division’s worth of men and the force was escorted by Cruisers, destroyers, two sloops and trawlers and began making good time and travelling around one hundred miles in nine hours.

It was just after midnight when the convoy was sighted by Kapitänleutnant Kraft’s SM UB-51. The convoy had taken every precaution with strict blackouts enforced but the moon was particularly bright and the sea so calm that the wash from the ship’s bows was clear to sea. The inevitable torpedo slammed into the Leasowe Castle amidships below the first funnel and after stokehold which killed several of the ship’s fireman as well as destroying one lifeboat and severely damaging another.

. Captain Sutton of the South Nottinghamshire Hussars felt the vessel judder through the darkness of sleep and he awoke. As he slowly became aware of his surroundings he asked one of his berth mates what was happening and was told; “if I didn’t get out pretty quickly I should pretty soon know what it was.”

Sutton pulled on a pair of shoes and his life jacket and ran for the staircase to the upper deck.

Up on deck where most of the men had been sleeping, action was taken quickly and efficiently with the soldier’s manning their action stations. Officers calmly paraded the men and began to fill the lifeboats in an orderly fashion whilst others were organised to prepare rafts. Gray-Cheape and Captain Drake moved to the bridge to coordinate evacuation efforts with the Ship's Master, Captain Holt. The liner had taken a slight list and was going down gently by the head which allowed the evacuation to be carried out at a steady organised pace.

Captain Holl gave orders for the vessel to be turned to full astern until all speed was lost and the vessel was stationary as well as sending emergency signals. Leasowe Castle’s Chief officer reported later that “The discipline of both troops and crew was superb, and the whole routine of men falling in on their stations worked to perfection.”

A full inspection of the vessel was carried out by candlelight (the lights were out) and water was found to be pouring in through the buckled and straining sides. The Chief, Second and Third engineers of the vessel were still at their station awaiting orders on the upper Engine platform. With water already covering most of the engine room they were relieved by the Chief officer and sent to the boats.

Fearing further attacks the convoy continued on its journey at full speed whilst the Japanese destroyer Katsura (often referred to as R) stood by to pick up survivors from the boats before sending the empty boats back to collect men from the water and rafts including the men from B coy (Warwickshire's) who had gone over the portside. The water was warm and still and Captain Sutton remarked that:

The night was wonderfully warm and I never felt cold, even in wet pyjamas. However some kind Naval officer fitted me out in a naval tunic an a pair of trousers, and of course I was the butt of many jests.

Another of the Nottinghamshire soldiers, Fred Marshal later spoke of climbing into a lifeboat with Sergeant-Major Legg whose trousers were so waterlogged that he thought someone was trying to pull him back into the water!

Other soldiers lowered themselves down ropes and into the water and made for the forty rafts and abandoned lifeboats however the greatest saviour was the sloop HMS Lily. At 1:45 a.m. the little warship came right up alongside the starboard side of the stricken liner and made fast with ropes so that she could take soldiers directly onto her own decks while the Katsura laid a smoke screen to protect the vulnerable vessel. A bear fifteen minutes later a loud rending noise filled the air with a bulkhead in the aft of the stricken vessel collapsing and suddenly the Leasowe Castle began to go down rapidly by the stern and her bows reared straight up on end. Deck hands on HMS Lily rushed to cut the lines with axes and knives separating the two vessels before the Leasowe Castle could take the sloop down with her.

The Chief Officer was sucked down with the liner as she went under but managed to come to the surface as the water reached the after funnel.

In his graphic report he describes what then met his eye - the ship standing up still more on end, her stem high above the water - the whole bridge structure crumbling in - a line of men leaping over the bows into the sea, their bodies silhouetted against the sky. Then she sank with a great noise. For a few moments there was silence, and then were to be heard cries for help.

Flares had been deployed and life rafts moved to try and pick up the men in the water whilst the lifeboats formed a cordon around them awaiting rescue.

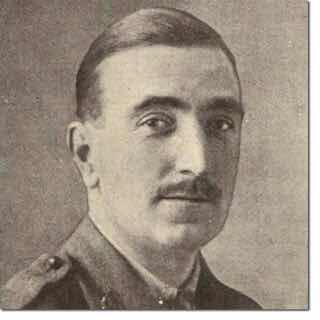

Lt-Col Gray-Cheape

HMS Lily was carrying some 1,100 men and her Captain passed an order to the soldiers to redistribute themselves around the decks to try and even out the vessel and avoid capsizing. Having avoided being struck by two further torpedoes she immediately turned for Alexandria and proceeded as quickly as she was able whilst the Katsura, HMS Ladybird and some of the trawlers stayed to collect survivors and by 11:30 a.m. they had left their station having saved the majority of the passengers. Of the some 3000 men aboard only 101 soldiers and sailors went down including the vessel's master, Captain Holl, and Captain Drake who were last seen on the bridge until the very end, in fact the majority of the casualties were believed to have been on the forecastle when the vessel quickly broke and dived sucking them down with her and only the body of Sergeant Vickers was washed ashore at Sollum. Lt-Col Gray-Cheape (pictured was seen in the water having gone over the side at the end and his haversack with personal items was recovered by Private Gould after the CO was killed by a falling spar.

One of the reasons for so many survivors was the well drilled nature of the ship’s company as Captain Holl was known to take lifeboat drill very seriously and whenever the vessel was at anchor he would drill his men in lowering, rowing, sailing and sea anchors as well as providing a number of the soldiers on board before leaving, in the handling of ship’s boats.

HMS Lily arrived at Alexandria by 7 p.m. and the surviving soldiers were given clean dry uniforms and blankets as well as much welcomed food and supplies in the port. A letter of sympathy and a subscription of funds to help pay for personal losses was received from the Commanding Officer of the Yeomanry base at Kantara, Lieutenant Colonel Cheesewright as well as a message of condolences from Brigadier General Kelly. Immediate order also had to be restored with command naturally passing to the South Notts CO, Major Warwick but unfortunately his head injury by a spar meant that command passed to Major Mills who was promoted to Acting Lieutenant-Colonel with Lieutenant Mercer as adjutant and RQMS Pardoe as Battalion quartermaster replacing the lost Lieutenant Hunter. By the following day the Battalion was back in order and reported for duty. Following re-equipping and reinforcements the Battalion reported having 937 men by the 12th June and received orders to embark aboard another vessel on the 14th June and left aboard the Caledonia on the 17th June for a much quieter journey across the Mediterranean.

The sinking of the Leasowe Castle could have been an absolute disaster and demonstrated the vulnerability of vessels to Austro-Hungary based U-boats even at this late stage of the War as well as the ineffectual nature of the Otranto Barrage at keeping the U-boats in check, it was an argument for the Allied Naval Commanders and something that was still being mulled over when the Austro-Hungarian fleet put to sea to attack the trawlers yet again - but that is another story.

Never knew the Japanese navy was operational in the Mediterranean. There’s a rabbit hole to go down!

de la Perière — in terms of tonnage sunk, the most successful submarine commander ever, almost all of it sunk in the Mediterranean by deck gun