Voices from the Formidable

New Years Day 1915 opened with a naval tragedy with the loss of the batleship Formidable which had been torpedoed by U-24 in the Channel. Heavy storms meant that few lives could be saved by the cruisers Topaze and Diamond and 547 out of 740 men were lost in the sinking.

There’s a full write up about it here…

On the 111th anniversary I thought I would share some of the accouts from survivors about the sinking.

Stoker Harold Smithurst quoted in Mansfield and North Notts Advertiser (29 January 1915)

Just a few lines to let you know I am getting on all right, as far as can be expected. I am lying in bed while I am writing this. I was sorry when we met with the awful disaster, because I never expected to get saved, and I know how much it would upset you and Aunt Clara and your Mother.

I have a lot to thank God for, because I have met with nothing else but misfortune that day. I never thought I should have reached the boat by jumping. It was my last chance and I jumped as I had never jumped before. And when I fell in the boat I thought I should have died straight away.

We managed to get away from the ship at last, but we were driven by the waves to the other side of the ship, and just as we got alongside the stern we were torpedoed a second time, so it just missed our boat.

We were in the boat ten hours after that, and you can tell what it felt like. I had only a shirt on and no drawers, and I did welcome the Provident [a fishing smack that picked up survivors], because I was the worst of the lot with being wounded badly.

They fairly threw me onto the deck of the Provident, because, with the cold and exposure, I was fairly useless. When we got to Brixham, they had to carry me ashore to the ambulance. And everyone was so kind to us. There are only two of us left in here now [Brixham Cottage Hospital], as the others have all gone back to Chatham. All the town turned out to see them off.

He also was quoted in the Nottingham Evening Post on 22 January 1915

I never expected to get safe. I have a lot to thank God for, because I met with nothing but misfortune that day. 1 never thought I should have reached the boat by jumping, but it was my last chance, and I jumped I never jumped before. When I fell into the boat I thought I should have died straight away. We were in the boat for 10 hours afterwards and you can tell what I felt like. I had only shirt and a pair of drawers, but no boots. I did welcome the coming of the Providence because I was the worst off of the lot with being wounded so badly. They fairly threw me on the deck of Providence, for with the cold and exposure I was useless.

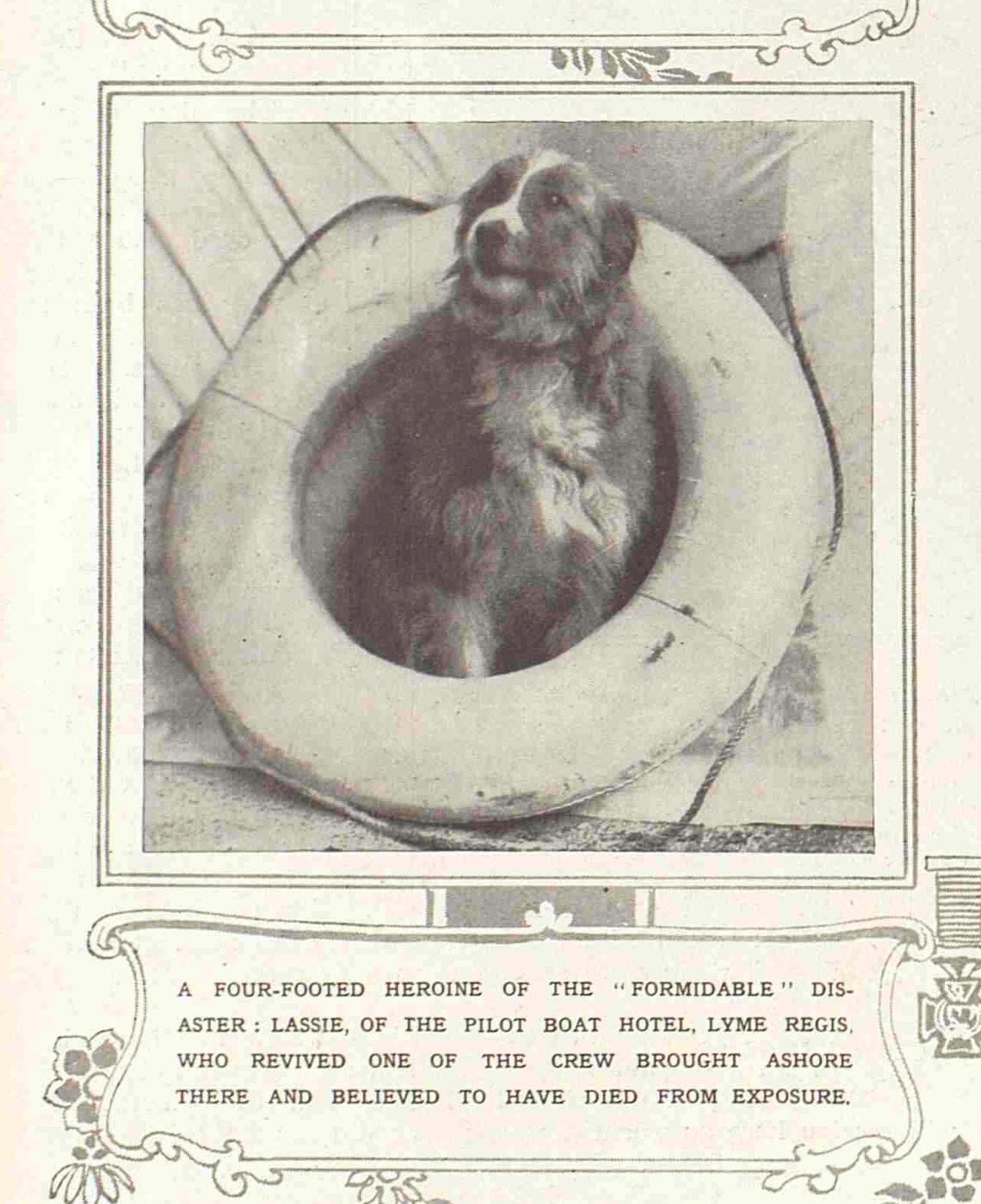

Able Seaman Cowan RFR was saved from death by the Collie Lassie (yes, that’s where the francise got its inspiration from) when the survivors of one boat were brought into the “Pilot Boat hotel” in Lyme Regis. The dead were laid out on the floor and left whilst awaiting collection but Lassie kept licking at Cowan’s face and laid with him…

One of the most moving incidents that occurred when about 48 survivors of the ill-fated H.M.S. Formidable were landed at Lyme Regis was the faithful conduct of a cross-bred collie named Lassie, belonging to Mrs. M. Atkins, of the Pilot Boat Hotel, it will be readily recalled that the survivors were taken to the hotel, and one of their number, named Cowan, it was thought, had succumbed the privations to which he had been subjected while being in an open boat for 22 hours, without food or water on a storm-swept sea. While Cowan lay apparently dead on the floor of the inn the dog approached him and settled down by his side. Lassie snuggled its body close to the man’s left side and commenced to lick his face assiduously. After while animation was thus restored to the seamen’s body, and he gradually recovered, thanks to the kindly attentions of the dog.

In recognition of its services on this occasion some of the dog’s admiring friends have presented it with a handsome silver collar, with padlock attached. The collar bears the following inscription: “Presented to Lassie by her admiring friends in Lyme Regis. The warmth of Lassie’s body revived the life of J. Cowan, one of the survivors of H.M.S. Formidable, who had been given up for dead. January 1st, 1915.” A medal has also been presented to Lassie for life-saving by the National Canine Defence League.

On Wednesday Lassie was honoured at Cruft’s Dog Show, London, where she was one of the 15 exhibits in the select circle of Cruft’s Canine Heroes’ League, and was awarded premier prize. Visitors to the show displayed a keen interest in Lassie’s noble work in restoring animation to the body of one of the Formidable’s survivors. At the show she probably did not understand the cause of her greatness, or why over her head there were placed a laurel wreath and a medal.

At the show Lassie was awarded a silver shield mounted on ebony and a silver medal. Inscribed on the shield was the following: — “Presented to Mrs. Atkins’ Lassie for saving the life of one of the crew of H.M.S. Formidable, 1st January, 1915.” Mrs. Atkins was, unfortunately, through indisposition, unable to accompany her pet to the show.

Quoted from the Taunton Courier 17 February 1915

Able Seaman Alfred Booth wrote a memoir of his time in the Navy and is quoted in the book “Before the Bells have faded” by M Potts and T Marks;

For some while, ships of the 5th Battle Squadron, of which Formidable was part, had been carrying out firing exercises in the Channel. On Thursday 30th December 1914 they had been ordered to proceed to Portland. Under the command of Vice Admiral Sir Lewis Bayly, Commander-in-Chief of the Channel fleet, in his flagship Lord Nelson, the squadron set sail as instructed. I felt weary. The crews had been exercising all day and I had only turned in two hours ago. Now it was New Years Day. Rumour had it that we would arrive at Portland on Saturday. With any luck we would be in time for the non-duty watch to be granted shore leave. I would welcome a run ashore. In my mind’s eye I planned a trip to Weymouth where I could revisit old haunts where me and my mates could enjoy a drink before returning on board. I was dozing fitfully and reminiscing when at about 2.30am. there was a terrific explosion.

The night was cloudy but visibility was clear up to two miles. The sea was choppy and the wind was getting up. The squadron had arrived between Portland and Start Point nearly 24 hours earlier but on the orders of the Commander-in-Chief had remained exercising in the area. The explosion came without warning. None of the British Squadron had been aware of the presence of a submarine and at first there was confusion as to whether or not it had been a mine. Formidable heeled over by at least 20 degrees. The throb of the engines stopped but was replaced by a roaring bellow of escaping steam as they rapidly lost pressure. A sudden hush prevailed as the bugler sounded the ‘still’ followed a few minutes later by ‘carry on.’ The sound of feet could be heard as men hurried to their stations. Suddenly there was a second explosion, bringing the ship to an even keel but down by the bow. It was becoming obvious that the stricken ship was doomed.

Fortuitously I was fully clothed. I moved hurriedly towards the upper deck, battled fiercely to maintain my balance as the ship continued to list to port. I eventually arrived at my boat station where I waited patiently for further instructions. The first boat to be lowered was smashed against the ship’s side and the occupants pitched into the ever roughening sea. Whilst the remainder waited their turn, any item which would float was hurriedly thrown into the sea. I suddenly realised I could hear the sound of a piano and men singing. Some of the younger crew members and indeed some of the not so young were feeling apprehensive.

Nevertheless discipline prevailed and they joined lustily in the singing. I wondered what has inspired a fellow crew member to think of others whilst the ship around him was sinking fast. The Captain had given the order to abandon ship. I looked around and decided to conform. I peered over the side. Waves were crashing against the stricken ship. It took a lot of effort to pluck up enough courage and jump. Too late, I realised I had neglected to bring my lifejacket with me. There was no time to think about that now. I kicked off my sea boots and murmured a few words of prayer, took a deep breath, closed my eyes and leapt into the angry waters below. The icy water encompassed my body as I hit the surface and continued to sink beneath the waves. Everything was going black. My lungs felt as if they were going to burst. My senses became dull and blurred. Lights flashed before my eyes. Then all went black. I regained consciousness to find myself being hauled unceremoniously into a sailing pinnace. “He’s still alive, ” I heard someone shout. “Only just. ” replied another. I attempted to mutter my gratitude but no words emerged. I was too cold and frightened.

I glanced around. The boat was crowded. It was being tossed in mountainous seas. The waves were reaching over thirty feet in height. One moment we were lost at the bottom of a trough, the next on the crest of an enormous wave. I estimated there were over sixty men in the boat which had been designed to carry far fewer. I spied a shipmate slumped near the side and managed a feeble wave. He acknowledged by a flicker of the eyes. There were six men on either side each pulling as best they could but already they appeared exhausted. By now we were about a mile from the stricken ship. Someone shouted “She’s going!” Those who could, looked in the direction of Formidable as she slid slowly but gracefully beneath the surface. Tears were apparent amongst many of those who witnessed her demise. I felt sick. I just wanted to die. Suddenly one of the oarsmen stopped rowing. He flopped over his oar and fell heavily to the bottom of the boat. His body lay awash with water which had poured in. One of the crew leant forward and shook his head. The man was dead. As gently and as reverently as they could, other survivors lifted the body and floated it over the side.Those who had the strength removed their sea boots and endeavoured to bale. It was a soul destroying evolution. As quickly as they removed the water it was replaced by twice as much. One man took off his jacket and with the assistance of a mate, placed it beneath the bilge water and gave it a sudden jerk, heaving the water over the gunwhale. This seemed to be effective and after a few repetitions the water had noticeably reduced. Two more men expired and their bodies were committed to the angry sea. The oarsmen were replaced by less exhausted men. Someone shouted above the noise of the storm “While there’s life there’s hope. Pull boys, pull. One, two three – pull!” I recognised him as Leading Seaman Bing. Master-at-Arms Cooper – the senior rating aboard – was remarkable and did what he could to maintain morale. He and the coxswain started to sing a ditty and gradually others joined in. The boat continued to be buffeted by the waves. The heavy rain became a mixture of hail and sleet. We were soaked. Suddenly someone in the boat shouted excitedly,

“There’s a ship.” I turned my head slowly. About a mile away I could sea the lights of what appeared to be a liner. As the boat crashed down, the lights vanished, but re-appeared shortly after the boat shot up towards the sky. Those who were able started to shout. They failed however, to rise above the crescendo of the storm. Gradually we realised they could not be heard, neither had we been seen. The ship continued on its way distancing itself further from the boat, oblivious to our plight. Despondently we sank back in the boat. More bodies were disposed of. Somebody had brought a blanket with him which, with the aid of a mop pole, was hoisted as a temporary sail. Daylight came. The storm continued unabated. Men continued to die.

The coxswain and Master-at-Arms Cooper carried on singing. Croaked voices accompanied them. The oarsmen battled on. By this time I had recovered a little and volunteered to do a stint on the oars. The man I relieved looked exhausted. We pressed on making little headway. Two more men died, others looked near to death. Night fell with no sign of land. I handed over my oar to another volunteer and sank back to ‘enjoy’ a fitful sleep. Then suddenly I was awoken by a disturbance in the boat and before I could come to my senses, realised that we were in a raging surf, with several men trying to pull the boat ashore. Thank God, I thought, we had by some sort of miracle reached the coast. When my eyes become accustomed to the light, I noticed through the gloom, lights and the shoreline. Gradually, the efforts of the men trying to get us ashore paid off. One of the boat’s occupants managed to throw a painter over the side which a police constable grabbed. Slowly they guided the boat towards the beach. The powerful waves did the rest, heaving it high on to the shingle.

The wind and rain continued to pound it, but our brave rescuers hung on. The more able crew members, including myself, passed our injured and fatigued comrades over the side, but some were too weak to stand unaided and collapsed on to the beach. More policemen arrived on the scene as well as several locals, who had been alerted and arrived ready to do what they could. Messengers were sent to inform the local medics and in no time at all, two doctors were available to treat the hapless men. Some of those stretched out suffering from exposure, had been brought round by assiduous rubbing and the use of stimulants. Several others however were beyond any human aid. Being one of the more fortunate, I helped as best I could and carried several of my shipmates to one of the nearby hostelries, which turned out to be the Pilot Boat Inn. The landlord and his wife immediately proffered their hospitality to the unfortunate men. Wet clothing was removed and replaced with temporary clothing, often too big or too small, and warm blankets. The wood fire in the largest room was soon blazing merrily and hot drinks and food were served to us by many willing hands. Slowly but surely, the men started to feel a bit more comfortable although many were still suffering from the shock of the ordeal. My shipmate and myself sat together offering each other mutual comfort and support.