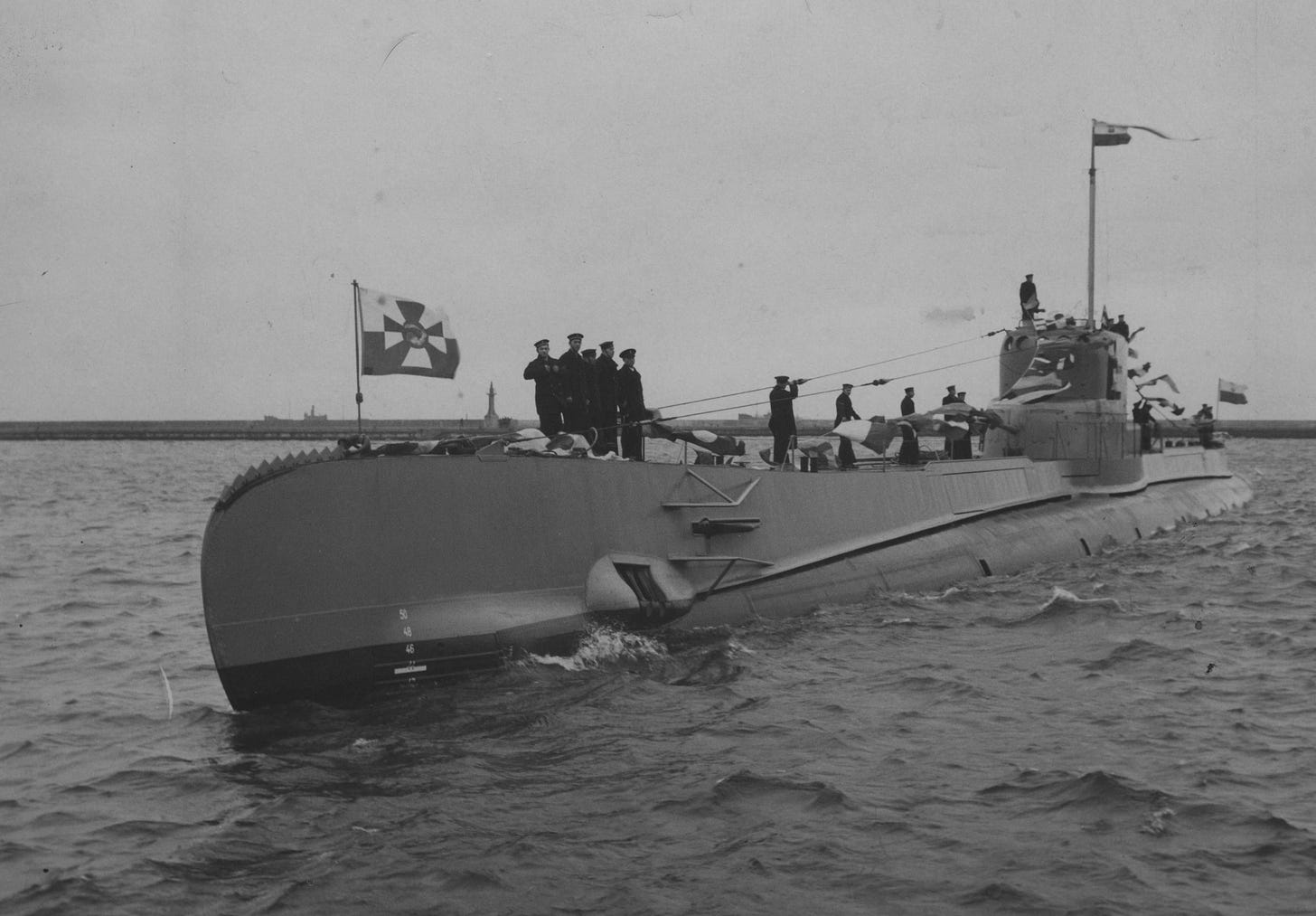

Possibly the most famous Polish submarine, ORP Orzel, was involved in a daring escape from Estonia and back through German policed waters and to Britain but it is a story not widely known here.

The Orzel’s campaign during the invasion hadn’t gone particularly badly, but considering the way the naval battle was going off the Baltic Coast in September 1939, it was somewhat inevitable that her War career would not be covered in glory but she did manage to escape the theatre.

You can see my longform article on the Polish Navy during the ‘39 campaign here.

At 01:30 on 14th September 1939 the ORP Orzel pulled into Tallinn harbour in Estonia having spent ten days limping with leaking oil from the Polish Baltic coastline.

During the Invasion, on the 4h September after an attack by a German aircraft which saw a near miss cause damage and rattled nerves, Orzel’s Captain, Lieutenant Commander Henryk Kloczkowski decided to move his submarine into the relative safety of deeper water, without the permission of his superiors. Whilst searching for German shipping they found the minesweepers M3 and M4 who immediately attacked with depth charges. With the German charges exploding around the submarine threatening to crack her hull open Kloczkowski used the deep water to crash dive to the bottom of the sea. Orzel had been heavily damaged in the attempt with all the lights aboard blown the crew sat in the dark waiting for the danger to pass. Kloczkowski took stock of the situation and decided that the only course of action open to him was to get to the neutral port of Tallinn

Rules laid out in The Hague convention meant that warships could use neutral harbours to resupply and repair but with limitations on time and amounts. Usually the time limit was twenty four hours to resupply or carry out minor repairs, enough to make the vessel sea worthy but would not increase their military capability. There was room to negotiate for longer time depending on the definition of “sea worthy.” Ultimately they just had to be able to operate under their own power without sinking but with the right officer and the right diplomatic pressure this could be changed.

Although the Estonian authorities did agree to uphold The Hague convention rules and were going to allow repairs to the Orzel’s compressor the Germans began to pile on diplomatic pressure to intern the submarine and her crew to remove them from the war so she could not slip back into the Baltic and cause havoc with German shipping.

The Estoian military attempted to board the Orzel on the first night with speed boats full of Estonian sailors pulling alongside so they could jump aboard. The Polish took steps to stop this by moving the submarine forward and leaving the Estonians falling into the harbour. Kloczkowski had a private interview with one of the captured Estonian officers and a few hours later another Estonian boat pulled alongside with the Polish Captain surrendering himself with two suitcases and a typewriter to go to an Estonian hospital.

There appears to be some conjecture as to his behaviour as he had had been suffering from an illness, possibly appendicitis or typhoid for the six previous days. Kloczkowski had also been suffering from poor morale since the beginning of the campaign and the crew believed he had had a nervous breakdown and was looking for a reason to get off ship. Admiral Unrung, the fleet C-in-C, had suggested to the crew that he was either removed in port and replaced or removed forcibly by the crew in preference of the First officer earlier in the month before they had withdrawn to Tallinn. The Officers and men were not happy with what seemed like the desertion of their Captain and Lieutenant Romanowski refused to believe that Kloczkowski “a man of strict rules, a great patriot, would betray” („człowiek surowych zasad, wielki patriota, miałby zdradzić”.)

Another attempt was made by the Estonian authorities during which an officer removed the Polish war ensign with the force successfully forcing the surrender as well as confiscating maps, navigational aids except for a guide of Swedish lighthouses, and dismantling the weapon's systems.

The Polish crew were not willing to accept this turn of events and the acting commander Lieutenant Jan Grunzinski and his first officer Lieutenant Piasecki began to plot an audacious escape attempt.

On Sunday 16th September Grunzinski sabotaged the torpedo hoist the Estonnians were using to disarm Orzel before they could remove the remaining six aft torpedos. With no other hoist available on a Sunday work was abandoned for the day.

Boatswain Wladyslaw Narkiewicz had been allowed by the port authorities to borrow a small boat to go fishing in the harbour. Right under the noses of the Estonian authorities he was actually measuring the depth of the harbour along a route they could use to escape.

That night all was set for the escape attempt at the soonest possible moment which happened at midnight on 18th September when a malfunction in the Estonian's lighting system plunged the harbour into darkness. As the crew began preparations to make way a surprise inspection occurred and an Estonian officer boarded and inspected the vessel. Either it was conducted in a half hearted manner or the officer was not paying that much attention but he found nothing suspicious and bid the crew a good night.

The crew quickly began their escape attempts. The two sentries on the dock were lured aboard, overpowered and taken prisoner whilst the mooring lines were cut with an axe before slipping away from the dock and made for the harbour mouth using Narkiewicz's measurements.

The lights suddenly snapped back on and the Estonians began sweeping the harbour for the missing submarine. One illuminated Orzel, and the Estonians fired using machine guns and light artillery damaging the submarine's conning tower. Larger guns were brought up but the authorities hesitated to use them for fear of seriously damaging the other vessels in the harbour. Despite the fire and temporarily getting grounded on a sandbar the Orzel managed to slip out into the Baltic.

Escape from Tallinn was only the first step though as they had to cross the “German lake” with no navigational equipment or maps so a plan was hatched to pull over a German vessel and acquire their charts. After three weeks of searching they gave up trying to find any German ships and instead, using the lighthouse book and a rough map the navigation officer drew from memory they made a break for Britain.

Before leaving the area the Orzel came close to the Swedish coast and put their two Estonian prisoners into a rubber dingy with a change of clothes each and 50 dollars and allowed to shore so they could make their way home to Estonia.

The Danish strait was heavily guarded and it took them two days to slip past the German patrols and out into the North Sea arriving off Scotland on the 14th October and sending out a broken English transmission for aid. They were escorted to port by a British destroyer. After refit and repair she entered service attached to the Royal Navy by January 1940.

The Soviets used the incident to challenge Estonian neutrality and when the tanker Metallist sank on the 26th September they falsely believed it was by Orzel. Both facets were used as an excuse by the Soviets to annexe the Baltic states the following year.

As for Kloczkowski he made his way to London from the USSR as part of Anders Army and was tried for desertion by a Naval court and found guilty, demoted to the rank of ordinary sailor and dismissed from the Navy. He was also sentenced to four years imprisonment but this was never carried out.