At 1:35 a.m. the fire engine pulled to a stop at the Vladimir Lenin Nuclear power station on 26th April as fires raged on the roof of the Reactor number 4 building and Lieutenant Viktor Kibenok deployed his men to join Lieutenant Volodymyr Pravyk’s power station fire unit to fight the fire. Within three months several of them would be dead, their bodies buried in lead coffins and encased in concrete whilst others would face long term medical issues caused by the extreme radiation.

Pravyk commanded the third watch at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Station’s fire brigade and had been in his office when the Chernobyl reactor blew and the hydrogen explosion ripped through the roof of the power unit sending flames 600 feet up in the air. The men outside who were having a smoke break immediately ran back into the fire station joining Pravyk and the others to man the fire engines. Within minutes they had deployed, it was 1:25 a.m. One of the firemen, Anatoli Zakharov noted the graphite on the floor and knew the dangers that would entail.

“There must be an incredible amount of radiation here. We’ll be lucky if we’re still alive in the morning.”

Pravyk and Leonid Shavrey climbed down from their vehicles and watched as the fire engulfed the bitumen covered roofs. They rushed into the Unit Three transport corridor then on to Four’s where they found a wounded and distressed plant worker who told them the fire was down in the main turbine hall. All telephone calls to the main Reactor Control Room are cut off by faulty telephone lines.

Shavrey was sent back to order the men to redeploy the fire engines at the southern end of the building closest to the Turbine Hall to start dealing with the fires whilst he continues to scout the area and find out more information about the fire and heads down to the Turbine hall. On arrival he found two turbinists, Busygin and Korneev who tell him that they have the situation under control there, despite the piles of debris and the damaged roof and instead they send him to the fires on the roof of the same hall.

Reinforcements arrived at 1:35 a.m. with nine men under Lieutenant Viktor Kibenok of the Pripyat Fire brigade. They were directed by Pravyk to move to the north side of the reactor building to fight the fires on the roof of the ventilation block and stop the fire spreading to the still operational Reactor Room 3. Kibernok then moved some of his men onto the roof of the auxiliary reactor system block to deal with the fires there. Extra engines from Chernobyl arrived under commander Grigory Khmel who was ordered to get in close to the reactor building and attach their hoses to the dry risers and cisterns to get the water up to the roof. Khmel is famous for reaching down and picking up one of the pieces of graphite from the cooling rods which proved the reactor had blown.

The site was taken over by Major Leonid Telyatnikov on his arrival at 1:47 a.m. officially reliving Pravyk with the latter leading a team of four men up the seventy meter climb of the escape stairs up to the roof of Reactor 3. These were Vasiy Ignatenko, Vladimir Tishura, Nikolai Vashchuk and Nikolai Titenok at 1:53 a.m.

Telyanikov took stock of the situation;

We surveyed the Unit 4 building. Through holes left by concrete panels smashed out we could see cable rooms, where no fires were observed. However, from the central reactor hall we clearly saw something like a blaze or glow... What was it? There is nothing except the reactor's "top face" in the central room, nothing was expected to burn there. We decided that it was the reactor itself that generated the glow. - Major Leonid Telyanikov

Following Pravyk’s report (at 2:05 a.m.) that;

Explosion in the reactor compartment of unit four!

Telyatnikov summoned the second shift of the Plant’s fire brigade to assist with the fire and reported that concerns were to be passed on to Kiev but the Kiev dispatcher had already notified the Ukrainian KGB after hearing Pravyk’s radio call.

Telyatnikov would move to the Unit 4 control room where the Deputy Chief Engineer, Anatoly Dyatlov wold him that the priority had to be the roofs of the Unit 3 ventilation block and at 2:30 a.m. a fresh team of three firemen went up the ladders to relieve Pravyk’s team.

Pravyk’s team had been busy in the forty minutes they had been up on the roof and had already called down for more water pressure for their hoses before climbing up onto the roof of the Ventilation block and looking down into the seething inferno that was the remains of the RBMK reactor where they were joined by Lieutenant Kibenok.

The super heated graphite from the control rods which had spewed out in the explosion, were starting small fires on the roof and Titenok and Tishura began trying to put those out, unknowing of the real danger they were in. The heat was melting the bitumen and hindering their efforts by causing their boots to stick and emitting thick black smoke laced with radiation that the men were breathing in. The superheated fuel on the roof was also problematic as the water from the hoses would evaporate before quenching the fire and some of the men took to trying to stamp out small pockets of glowing fuel. After twenty minutes Tishura collapsed and started violently vomiting and unable to stand, Titenok would follow shortly. Ignatenko helped to carry both men down to the ground where Telyatnikov ordered them taken to the ABK2 (administration block) and await an ambulance. Pravyk would follow them at 2:15 a.m.

Pravyk descended. He looked terrible, with a round, red face, round bulging eyes. Wheezing. He went to the ambulance - Telyatnikov

Pravyk reported that the roof of the Third Power unit was now extinguished and Telyatnikoc would climb to the roof of the turbine hall to tell firemen present to firewatch from there and await further orders, later stating that;

The most frightening thought we all had was that we wouldn’t have enough strength to hold out until reserves came and prevent the fire from getting out of control. About an hour after the fire began, a group of firefighters with symptoms of radiation exposure were taken down from a rooftop close to the damaged reactor. When I approached five men to take up the position, they rushed to the rooftop almost before I could get the words out of my mouth. - Leonid Telyatnikov

At 2:40 a.m. the six firemen were being taken to Sanitary Unit No. 126 in Pripyat for their initial treatment. It was here that their uniform and gear was removed and placed in the basement of the hospital where they remain to this day, still heavily irradiated.

A dosage of radiation needed to kill a healthy adult is 400 REM or 400 Roentgen for an hour but the firemen under Pravyk were exposed to was staggeringly 20,000 Roentgen from the graphite on the roof and Uranium fuel and 30,000 Roentgen around the exposed core which is fatal after 48 seconds. Allegedly the amount of radiation they were exposed to was enough to turn Pravyk’s eyes from brown to blue and Nikolai Titenok was said to have developed radiation blisters on his heart. Zakharov was later hospitalised in Kiev and told he had absorbed 300 REM.

That’s what they wrote down. But only God really knows what my dose was.

Pravyk is considered to have received the highest dosage of radiation with 1370 REM

As the sheer horrors of the disaster became clear and the nature of the injuries to the firemen was realised the men were transferred to Borispol airport, Kiev, on the 26th April and then flown to Moscow’s No. 6 hospital which was under the Soviet Nuclear energy department where specialised radiological departments could be used.

The suffering of the men was horrendous.

Ignatenko would excrete blood and mucus twenty five times a day, coughed up fragments of his organs and eventually died on the 13th May, Through his suffering his wife, Lyudmila, was by his side;

They couldn’t get shoes on him because his feet had swelled up. They had to cut up the formal wear, too, because they couldn’t get it on him, there wasn’t a whole body to put it on… My love. They couldn’t get a single pair of shoes to fit him. They buried him bare foot. - Lyudmila Ignatenko

Part of the condition is a reprieve from suffering and the patient begins to think they are getting better before it comes back with a vengeance. Pravyk wrote to his wife that;

Nadya, you're reading this letter and crying. Don't dry your eyes. Everything turned out okay. We will live until we're a hundred. And our beloved little daughter will outgrow us three times over. I miss you both very much... Mama is here with me now. She hotfooted it over here. She will call you and let you know how I'm feeling. And I'm feeling fine

The main damage was to the bone marrow which lowered white blood cell count leaving the men vulnerable to infection whilst digestive and respiratory systems looked close to collapse. Some of the men were given bone marrow transplants and or blood plasma but for some it was too late. Pravyk’s brother, who had come forward to give him a transplant, was told to stand down as it was already too late. His medical report read;

Pravyk Vladimir Pavlovich, 23 years old. head of the HPV-42 guard, was treated at the clinic of the Institute of Biophysics (Moscow) from April 27 to May 11, 1986. The patient suffered from acute radiation sickness of extremely severe degree : oropharyngeal syndrome, severe depression of hematopoiesis. pulmonitis, radiation burn of the entire skin of 1st degree and 3-4th degree of the skin of the face, neck and hands. Toxemia. Toxic-septic lesion of parenchymatous organs, pulmonary edema, cerebral edema, The disease arose and the death occurred due to the direct participation of the patient in the accident at ChNPP. The conclusion was issued to the wife of the patient for presentation at the place of residence. Chairman of the Expert Council A.K. Guskova, secretary L.N. Petrosyan

The respiratory damage might have been caused from breathing in the radioactive vapours that were eminanting from the open reactor whilst Pravyk and the others were up on the roof.

By mid May five of the men were dead along with some of the Chernobyl staff; Akimov, Baranov Degtyarenko, Ivanenko, Konoval, Kudryavsev, Kurguz, Lelechenko and Lopatyuk and many others who would die over the coming months and years.

With their bodies still heavily irradiated they were placed in lead coffins and interned in Mitinskoe cemetery in Moscow under a lot of concrete to contain the radiation. The majority of their equipment was later buried in concrete in vehicular mass graves with many other pieces of equipment whilst others were left to rust and decay including tractors, bulldozers and railway rolling stock.

The fates of the firemen were:

Mikhail Golovnenko - died 2005

Vasily Ignatenko - died 13th May 1986

Grigori Khmel - died 8th January 2005

Victor M Kibenok - died 11th May 1986

Oleksandr Petrovsky - still alive in 2021

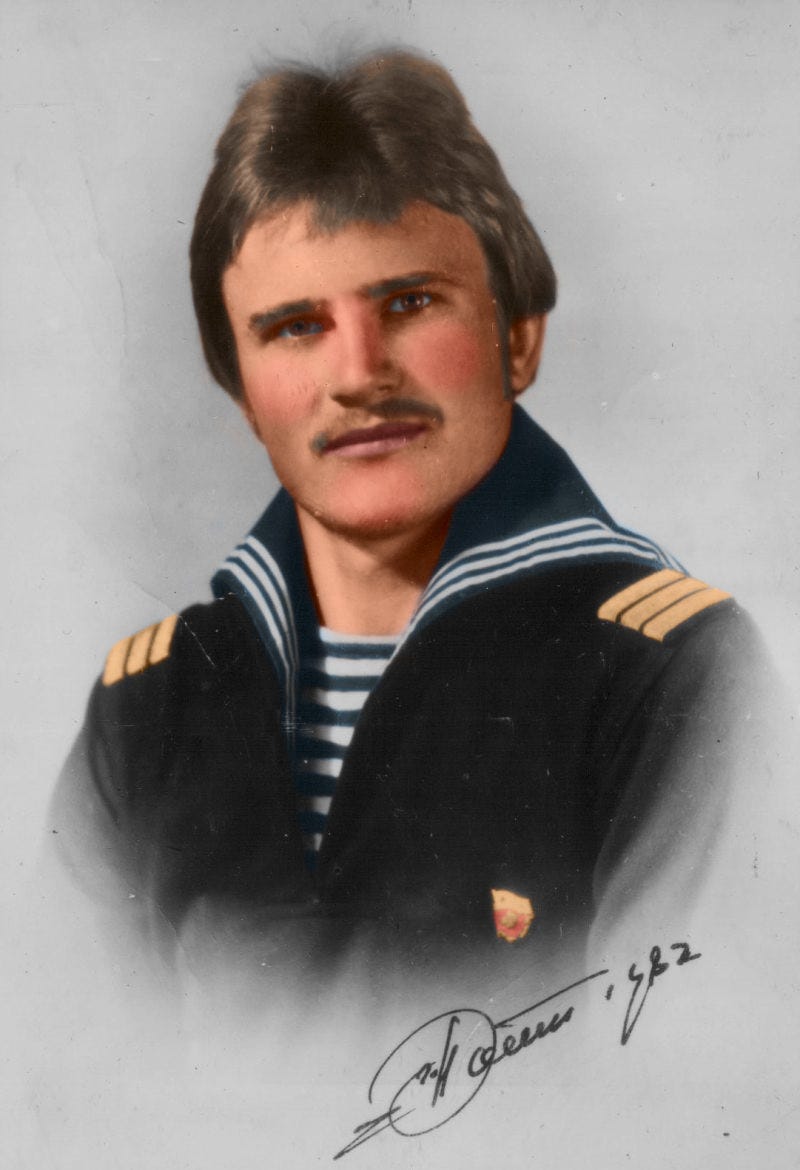

Vladmimir Pravyk - died 11th may 1986

Vladimir Prishchepa - died 1993

Leonid Telyatnikov - died 2nd December 2004 (cancer)

Vladimir Tishura - died 10th May 1986

Nikolai Titenok - died 16th May 1986

Mykola Vaschuk - died 14th May 1986

Ivan M Shavrey - died 20 November 2020 - Covid

Leonid Shavrey - died 14th April 2012

Petr Khmel - Alive as of 2024

Anatoly Zakharov - Alive as of 2022

A grateful Soviet Union would reward the men posthumously with Kibenok becoming a Hero of The Soviet Union, Ignatenko receiving The Order of the Red Banner and the Hero of Ukraine whilst Pravyk received Hero of the Soviet Union, Order of Lenin, Ukrainian Star of Courage.

The world, although remembering the Chernobyl disaster as an awful loss of life and the long term effects of the site - especially through the HBO series and Call of Duty games but how widespread it is I’m not sure, I know my children hadn’t heard of it where as people of my generation remember seeing it on the news or, as in my case, remember being kept inside at school as a radioactive cloud was due to pass over but the sacrifice of the firemen who went in without any form of protection, arguably unknowing of what they were charging into or dedicated to stopping the spread of the fire to the other reactor halls.

A friend of mine from Ukraine told me some survivors were sent to hospitals in Cuba. She pronounced "Cuba" as Spanish speakers do.