Obvious... even to a numbskull

The Mediterranean, the flight of the Goeben and Troubridge scandal

The Mediterranean Sea was going to be the one of the most active naval theatres of war during the Great War and in August 1914 it was where the first embarrassing defeat was handed to the Royal Navy.

As the July crisis continued the two sides began to take stock of the naval situation and what their objectives might be.

For the French it was straight forward. They needed to transfer the Army Division in Algeria to the South of France as quickly as possible using the fleet for protection. How they did that was up for debate though. Afterwards their fleet was free to attack any Central Powers vessels.

Britain was not getting involved. The Liberal Government did not really want to get entangled in a War between European powers on the mainland.

BUT

They did start to mobilise vessels for action based at Malta and monitor what everyone else was doing.

Germany had limited vessels, two in fact, the battle-cruiser Goeben and light cruiser Breslau under the command of Vizeadmiral Wilhelm Souchon who wanted to get into action straight away. He knew that Germany’s success in the war hinged on a speedy victory and his ship held a vital key to that. If they could decimate the French troop ships it would mean vital men would not be in Southern France. He implored the Austrian Commander-in-Chief, Admiral Haus, to send a sizable force to meet him at Messina in Sicily and together with an Italian force they would sail out together, united, and defeat the French fleet.

Haus was non-committal. Though Souchon’s plan had merit it did mean leaving the Adriatic undefended, risked his irreplaceable ships and what about Italy? While his ships were away Italy might attack

Italy was even more non-committal and not just to Souchon but to the whole Central Powers agreement and there was a general lack of interest in getting involved at all and were busy looking across the Adriatic in case the Austrians decided to attack them as well.

Souchon arrived in Messina on the 2nd August and began recoaling but the port and its facilities were not what he had hoped for and there was not much in the way of coal for him to purchase but there was a German flagged liner, General, in port. Souchon commandeered the civilian vessel, disembarked the passengers before taking a sizable chunk of her coal and crew to bring his vessels up to war footing. Orders were also given to remove all unnecessary trappings and furnishings, especially flammable things, from the two warships and to store these in the port whilst he awaited the arrival of the Austrians.

At 6 p.m. a telegram arrived confirming that Germany was now at War with France.

The game was afoot and Souchon took immediate action knowing that his being in Medina had already been reported to the enemy, and with it looking more and more unlikely that the Austrians were not sending anyone. Goeben and Breslau slipped out of harbour at 1 a.m. on the 3rd August and headed north to throw off any observers at 16-17 knots before turning along the coast and passing out the north end of the Straits of Messina and changing course for Algeria. At the same time orders arrived marked Secret and Urgent but Souchon decided not to open them until he had carried out his initial strike.

In the small hours of the morning of the 4th August a Russian flagged warship entered Philippeville port and then opened fire. After fifteen shells the fire stopped and the warship departed and Goeben raised the Imperial Naval flag. Souchon was disappointed that Phillippeville had not held the convoy’s vessels as he had hoped nor was there a body of soldiers waiting for embarkation or supplies. Reports from Breslau at Bone echoed his experiences and he ordered both ships to head for Messina again.

Where were the French though?

There was a bit of an argument going on between the French government and their Commander of the Mediterranean fleet, Admiral Augustin Boue de Lapeyrere, as to how best escort the African troops to Europe. The Government wanted the army bringing up to Toulon to come as quickly as possible and wanted the fleet to be deployed in a cordon across the 458 nautical mile distance. Lapeyrere felt that this was a very vulnerable position and that if Goeben or any Austrian cruiser could sneak through the gaps they could cause untold damage to the transports or gain local superiority at one point which would allow them to force the corridor. On 3rd August the French fleet left Toulon to head to Algeria and once they arrived they would begin embarking the troops which was in complete disregard to the Government’s orders. An officer was dispatched at the same time to Paris to explain the Admiral’s position and the Ministry were forced to accept that Lapeyrere had complete charge of the fleet.

The British were not doing very well though.

One of the continuing themes through my works will be criticism of the First Sea Lord of the Admiralty, Winston S. Churchill, who often makes things more complicated than they need to be and needlessly meddles in the affairs of the Sea admirals and the Goeben affair is the first major red flag of what will follow over the course of the next year.

As the situation in Europe is spiralling, Churchill took stock of the tactical situation in the Mediterranean and decided to get the Royal Navy's forces ready for action and in positions where they could be most effective. A long and complicated list of instructions were sent through to Malta where the theatre commander, Admiral Berkley Milne, was to enact them.

Admiralty to Commander-in-Chief, Mediterranean. 30th July 1914

It now seems probable should war break out and England and France engage in it, that Italy will remain neutral and that Greece can be made an ally. Spain also will be friendly and possibly an ally. The attitude of Italy is however uncertain, and it is especially important that your Squadron should not be seriously engaged with Austrian ships before we know what Italy will do. Your first task should be to aid the French in the transportation of their African army by covering and if possible bringing to action individual fast German ships, particularly Goeben, which may interfere with their transportation. You will be notified by telegraph when you may consult with the French Admiral. Except in combination with the French as part of a general battle, do not at this stage be brought to action against superior forces. The speed of your Squadrons is sufficient to enable you to choose your moment. You must husband your force at the outset and we shall hope later to reinforce the Mediterranean.

Milne was not the most inspiring fleet commander and some of his harsher critics would point to his only getting a flag command being due to his time aboard the Royal yacht and having influential friends such as Queen Alexandria. He was considered dull witted, slack, ultra-snobbish and said once that:

They pay me to be an Admiral, they don’t pay me to think.

In the long, relatively, peaceful Victorian period having such a fleet commander would not be an issue as you could always rotate him away from the major theatres of war but in 1914 he was a liability waiting to happen. His direct subordinate was Admiral Ernest Troubridge who was a much more capable but cautious officer.

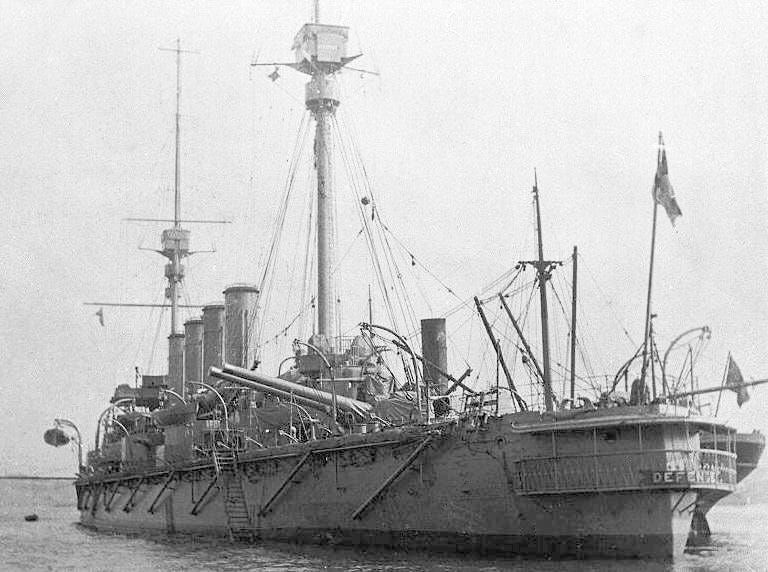

When the above orders were delivered Troubridge and Milne met to discuss the orders and the First Cruiser Squadron consisting of the Armoured cruisers Defence, Black Prince, Warrior, Duke of Edinburgh and light cruiser Weymouth with a group of destroyers to the mouth of the Adriatic. To give them some firepower the battle-cruisers Indomitable and Irrdefatigable were dispatched with him. Troubridge made it clear to Milne that he believed, that from the wording Goeben was a “superior force” to which Milne agreed.

On the 2nd August orders would follow from London to recall the battle-cruisers as they believed Souchon would sail west and was a menace to the French convoys. Reluctantly Troubridge dispatched the two ships now powerless to do anything should heavy units of the Austrian Navy put to sea.

Unknowing of where Goeben might be the light cruiser Chatham was sent to Messina on the 3rd August to see what they could see but the Germans were found to have gone. One of her crew, Albert Masters, recorded that:

It became known in the ship that our quarry was the Goeben and Breslau and fortunately for us they’d gone! When I say fortunately I mean we were in no position to tackle the Goeben she had 11” guns she would have blown us clean out of the water!

At 10:30 a.m. which was about three hours before the British ultimatum was delivered to Germany a strange coincidence occurred with the British battle-cruisers encountering Goeben and Breslau heading in the opposite direction. Neither squadron was sure of their opposite number’s intention and trained their turrets at each other in the passing and neither side gave the customary greetings signals with each waiting to see if the other would make a hostie move but as soon as they had passed each other Indomitable and Inflexible turned and gave chase. Souchon ordered his vessel to get as much speed up as possible so as to try and escape their pursuers and deep in the bowels of the battle-cruiser the men toiled to raise steam in the heat of the Mediterranean summer with boilers that were still far from optimal. The heat began to cause issues as men passed out from the heat exhaustion and were moved to the decks to recover in the winds and fresh arms were put into the boiler rooms though at one of the most critical moments there was a mechanical error which ruptured one of the lines and a cloud of red hot steam scalded four men to death but the Germans pressed on.

The British battle-cruisers were also pressing as hard as they could but their engines were in need of maintenance and their bellies scaping which were slowing them down and eventually they lost pace and Goeben managed to pull far enough ahead that only the light cruiser Dublin could manage to hold position until 7:37 p.m. when Captain Kelly was forced to send a message to Milne:

“Goeben out of sight now, can only see smoke, still daylight.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Chris’s Naval History Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.