The Franklin expedition to find the Northwest passage is a story that still grips the imaginations nearly two centuries later which has been aided by the book and series “The Terror”. There were very few things left behind by Sir John Franklin’s two ships, Terror and Erebus beyond scattered human remains, two shipwrecks (only recently found) the Victory point cairn with letters but more importantly the three graves on Beechey Island for three members of the crew (and one for a would be rescuer, the French naval officer Joseph Rene Bellot). I first became aware of the story when I was about ten years old reading about mummies including ice mummies and I stared down at the face of John Torrington and it was then that I became interested in the story. Coincidentally my eldest boy, Ollie, came home from school aged 9 and asked me if I knew anything about the Franklin expedition - things got nerdy quickly!

As a trigger warning I will be placing a picture of Harnell as he appeared when they carried out the 1985 exhumation further down.

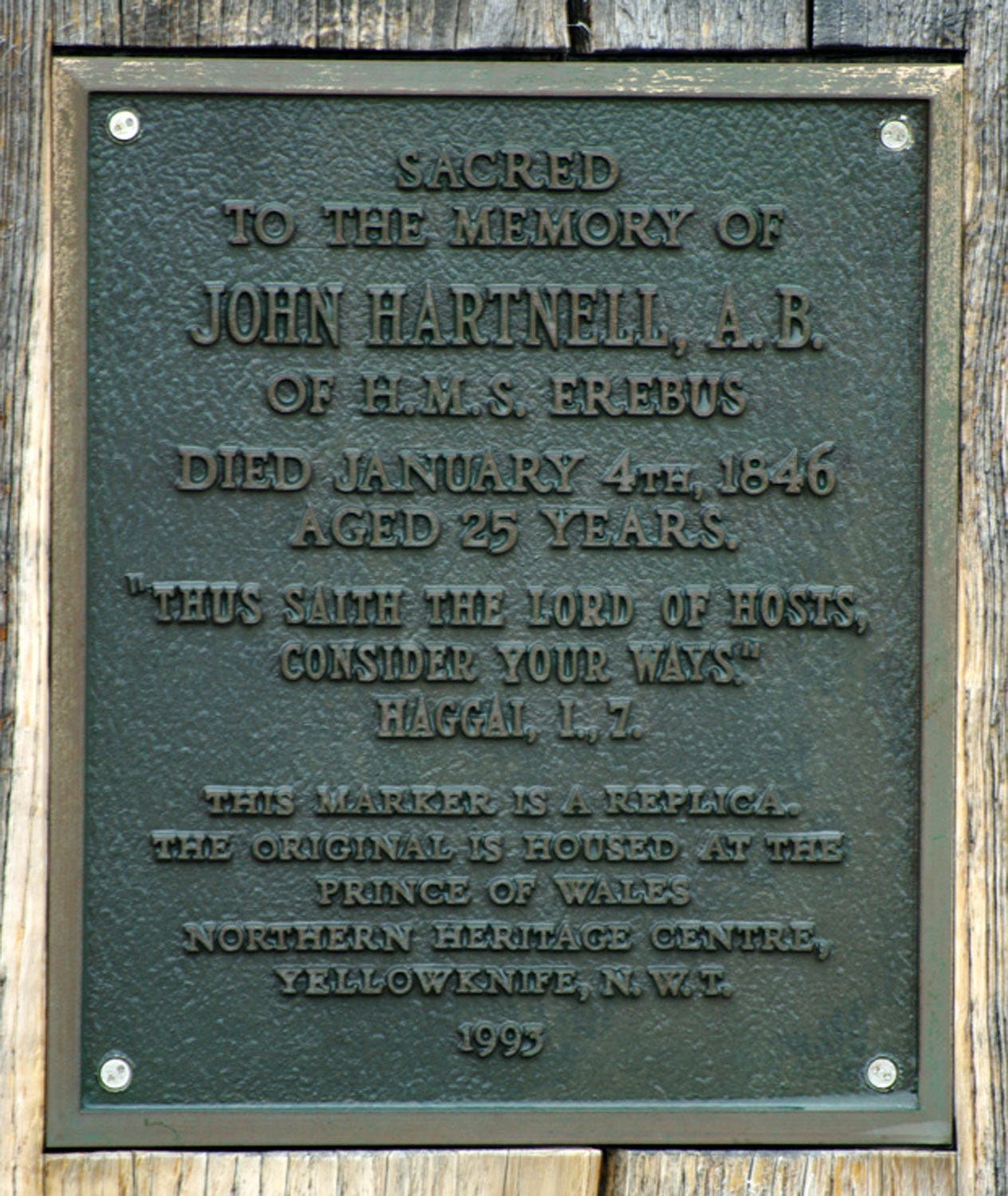

The three graves are for John Torrington, John Hartnell and William Braine who had all passed away in 1846. They are the members of the crew whose fate was definite and for John Hartnell, he was a long way from Gillingham.

John had been born around 1820 in Gillingham, Kent to Thomas Hartnell, a shipwright at Chatham dockyard and Sarah nee Friar who had been married at Frinsbury church on 9th October 1815. The couple seem to have waited to have children for a few years as John was the first of six children (five survived to adulthood) and included his brother Thomas junior, and was baptised in the parish church of St Mary Magdalene on Gillingham Green on the 16th July 1820 and by the 1841 census he was a shoemaker.

By September that year he had signed up to the Royal Navy and served aboard the sixth rate frigate, HMS Volage with his pay allotted to his younger sister rather than his mother which was more usual and what his brother Tom had done. He was 5’11” tall with brown eyes, a sallow expression and dark brown hair according to his attestation papers in 1841. His four years saw him being promoted to Able Seaman and he was paid off on 1st February 1845.

Soon after he and Tom signed up to the Franklin expedition aboard Erebus and the pair sailed away on Franklin’s flagship (under Captain James Fitz James) but he was dead by the following 4th January.

When Owen Beattie led his expedition to Beechey Island to examine the bodies in 1984 and started examining the grave of Hartnell, they found that at some point his grave had been disturbed which could have proved problematic to this investigation. Indeed when they began exhumation they found the permafrost harder than it had been when they had exhumed Torrington and there were wood fragments and blue material in the earth and, also unlike Torrington, the coffin was only 38 inches below the ground. Further evidence of disturbance included damage to decoration on the coffin and a gaping hole midway down the right hand side and the lid was prized open but not by vandals but carefully and respectfully and there was no plaque on the coffin possibly removed by whoever had opened the grave. The face that was revealed as they melted the ice gently with water showed a sunken or lost right eye, thick dark hair and the face of a grizzled sailor whose features were wracked in pain.

Hartnell had been covered in a shroud but the right for arm had been exposed showing a clothed arm though his arm also looked damaged.

The first person to attempt an exhumation was Sir Edward Belcher’s expedition in 1852 but the thickness of the permafrost was so strong they gave up quite quickly and it wasn’t until Inglefield’s expedition, sponsored by Lady Jane Franklin, in November that year that an exhumation and examination was carried out.

This sad emblem of mortality - the grave- soon met my eye, as we plunged along through the knee-deep snow which covered the island. The last resting place of three of Franklin’s people was closely examined; but nothing that had not hitherto been observed could we detect. My companion told me that a huge bear was seen continually sitting on one of the graves keeping a silent vigil over the dead. - Inglefield

Inglefield was keen to examine the body, perhaps thinking of Lady Franklin’s wish to know of the fate of her husband and his men, and was hoping to find any clue to what may have caused these deaths and whether it would have effected everyone else. The exhumation was carried out at midnight with six officers and Doctor Peter Sutherland in attendance so that the enlisted crewmen would not find out incase it cause disquiet amongst them. Due to the time constraints, the cold and conditions Sutherland and Inglefield only managed to work on the right hand side of the face and right arm hence the cuts in the shroud and exposure of the right arm. In a letter, Inglefield wrote about the autopsy.

My doctor assisted me, and I have had my hand on the arm and face of poor Hartnell. He was decently clad in a cotton shirt, and though the dark night precluded our seeing, still our touch detected that a wasting illness was the cause of dissolution. It was a curious and solemn scene on the silent snow-covered sides of the famed Beechey Island, where the two of us stood at midnight. The pale moon looking down upon us as we silently worked with pickaxe and shovel at the hard-frozen tomb, each blow sending a spur of red sparks from the grave where rested the messmate of our lost countrymen. No trace but a piece of fearnought half down the coffin lid could we find. I carefully restored everything to its place and only brought away with me the plate that was nailed on the coffin lid and a scap of the cloth with which the coffin was covered.

Beattie would cover Hartnell and replace the coffin lid before placing an orange tarpaulin over the coffin before burying him again. They would return to carry out a more in depth investigation of his grave the two years later.

When they returned, and Beattie’s team again uncovered the face of Hartnell it was in the presence of his great-great nephew, Brian Spenceley.

This new examination shows that the right eye had definitely shrunk but the left was also showed signs of shrinking too and it was hypothesised that the shrinkage of the right eye was caused by the 1852 exhumation where only the right side of the face had been exposed.

Hartnell was wrapped in a white shroud which covered him from his shoulders down which had a tear in it exposing the damaged shirt sleeve of his right arm and further damage to his chest wall by wooden fragments of coffin were also present - again thanks to the 1852 dig.

Hartnell was wearing a toque like hat and his head rested on a frilled pillow filled with wood chippings, a woollen blanket lay beneath him and his arms were bound to his body with light brown wool though the 1852 inspection had left his right hand unbound.His white and blue striped shirt, which had actually belonged to his brother Tom (according to the initials marked upon it) was missing a few buttons and the button holes tied up with string. He was layered up to protect from the cold and had a woollen undergarment and a cotton undershirt but he was stripped from the waist down.It was the legs that betrayed the first possible cause of death - they were shrunken and emaciated by illness

An X-ray showed that he had suffered a compression fracture in one of his lower neck’s vertebrae, there were some malformities as well but nothing too bad but there was a bone in his left foot which could have Osteomyelitis and this could mean he was more likely to get blood poisoning.

When they removed his clothing they found an upside down Y incision which had been done before burial by one of the Erebus’s surgeons, it was suggested that it might be Doctor Harry Goodsir who was an anatomist however when he had returned the organs he had done so as a mixed up mess rather than placing them in their proper place - I mean he was already dead and as long as they were back in there…

There is quite a lot of debate as to the lead poisoning endured by the crew from the shoddy tinned food or botulism and hair samples did show large concentrations of lead but that is beyond the scope of what I’m writing today but according to a 2015 study it suggested that zinc deficiencies and malnutrition were more likely the cause.

Back in Gillingham the admiralty wrote to his younger brother Charles in 1854 to inform them of his death and burial at Beechey Island but that John was “In debt to the crown £117 4s 8d” which is a hell of a lot of money for 1854 but there was no reason written as to why. The Navy withheld his, and Tom’s pay from the family as well as the Arctic medal which was finally presented to the family in 1986.

A headstone was erected at St Mary’s church for both brothers with the inscription:

Died in the execution of his duty, as seaman on board H.M. Ship Erebus in the ill fated expedition under Sir John Franklin. His remains lie buried on Beechey Island in the Arctic seas.

Having lived near St Mary’s and spent a lot of time wandering the graveyard I’ve not found it and most of the graves were cleared away in the 1970s when the land was redesignated a park. It may be in the Church itself so I will have to go and have another look sometime.

He was remembered by his sister who called one of her sons John Hartnell Solton and family rumours and oral tradition told of two brothers who had disappeared into the arctic.

Other than Franklin expedition nerds like me there probably aren’t many Gillingham locals who know of one of the Medway’s lost sons and as far as I know there is nothing to commemorate either of the Hartnells