Falklands preview 1: The British moves

As darkness consumed the surviving ships at Coronel, the competing Admiralties moved closer to the edge of their seats. The Germans claimed this a stunning victory and were now asking the question; could von Spee make it back to Germany?

For the British though, it was a horrendous embarrassment, the first naval defeat since the War of 1812 and the London Admiralty was exposed as out of touch with accusations of poor planning being levelled.

At the very top, the First Sea Lord, Louis von Battenberg, had realised a few days beforehand that he could not adequately fulfil the post and that his German heritage did not inspire confidence. There were also so many bushfires to tackle, the Kongisberg, Emden, Leipzig and von Spee’s squadron coupled with offensive operations around the globe and maintaining the Home Fleet, tackle U-boats and work with Churchill. The first cracks had started with the loss of the Cresseys in September and on the 28th October he wrote to Churchill that:

I have been driven to the painful conclusion that my German birth and parentage have the effect of impairing my usefulness in the Admiralty. I feel it my duty to resign.

Churchill is far from blameless and despite his keen enthusiasm and belief in the Royal Navy he was a civilian whose only military experience had been as a cavalry officer and as a war correspondent. Instead of leaving things to the professional sailors Churchill was immersed in every tiny detail down to one cruiser having to send a signal to London requesting permission to dole out extra ram ration which is an issue for the Captain to decide. Churchill also revelled in the grand strategy of controlling ships across the globe and explaining at length via wireless what he wanted admirals to do, overruling the men who knew better and should have been allowed a freer hand in deciding their options and fleets. The whole Canopus issue is a clear example of this as on paper she was a formidable addition to Craddock’s force but the shortcomings were overlooked by Churchill and he browbeat Craddock, who knew the situation more clearly. So hung up on the idea of Canopus that on the 3rd November, having heard nothing of Craddock, Churchill turned to Fisher and asked;

You don’t suppose he would try to fight them without Canopus?

Another mark on Churchill’s character was that at a critical moment, when the Leipzig and Dresden had disappeared in the late summer he had disappeared to take personal command of the Naval Brigade in Belgium and Asquith had to summon him back.

Next down was Admiral Sturdee who was massively overwhelmed at the Naval War Staff as he refused to delegate to junior officers and wanted to see every piece of paper and write all the signals himself. Work, understandably, built up and things slipped through the cracks. With the appointment of the new First Sea Lord, Lord Fisher, Sturdee was the first to go on the 4th November. This was partially motivated by Sturdee’s faults and also from sheer personal dislike by Lord Fisher.

It had been Fisher’s insistence that had seen Defence ordered to Craddock’s flag, yes it was too late but it was a positive move. On the news of the defeat Fisher spun into action with a willing Churchill, blood would be paid.

Sailing south from the battle the Glasgow was attempting to meet up with the Otranto and Canopus before the Germans could hunt them down, Despite being hit several times by the Dresden and Leipzig and having one compartment flooded the cruiser was in good fighting order. Captain John Luce wrote in his report of the battle that;

The spirit of my officers and men is unimpaired by this serious reverse and their unanimous wish is that the ship may take part in further operations against the enemy.

The Canopus had received a partial wireless transmission from Good Hope which was just going in to combat some 250 miles from their position and Captain Heathcoat Grant ordered more speed to try and join Craddock but four hours later at 8:45 p.m. the Glasgow signalled them.

Feat Good Hope lost, our squadron scattered

Grant would later write that;

It was a most dreadful shock to everyone, and I cannot describe my own feelings except that at first I refused to believe it.

Lieutenant Harry Bennet would record in his diary that;

Had we not had the engine room defect… or had we been 24 hours earlier we could not have failed to have been on the scene of the action and possibly helped “Good Hope” and “Monmouth”. It is a dreadful (thing?) to us to think that “Good Hope” is lost full of good friends. Some sadder still will think that 750 women in a few minutes in all probability were widowed.

Having not heard from anyone else but Glasgow by the following day Canopus rounded up the collier convoy and redirected them to Stanley.

The Chilean wireless stations were sending a lot of messages for the Germans which Bennet would write in his diary was a betrayal as he had thought that the Chileans and British had always been friends but the increased radio messages jammed the British signals slowing news arriving in London of the defeat and status of the surviving ships. It was not until the 6th November that Glasgow could send a full report and assure London that they, Otranto and Canopus had survived.

Action was already being taken by Fisher though as he was fully prepared to send two battle-cruisers from the Grand Fleet to send to Stoddart at Montevideo and a third to be based at Halifax. There was hesitancy about numbers and whether they could be sent without seriously affecting the balance of power in the North Sea but with HMS Tiger about to be deployed and the Queen Elizabeth, Emperor of India and Benbow almost ready it was considered a worthwhile risk. At 12:40 p.m. on 4th November a comunique was sent;

Order Invincible and Inflexible to fill up with coal at once and proceed to Berehaven with all dispatch. They are urgently needed for foreign service. Admiral and Flag-Captain Invincible to transfer to New Zealand. Captain New Zealand to Invincible. Tiger has been ordered to join you with all dispatch.

Twelve hours later Churchill telegraphed Jellicoe;

From all reports received through German sources we fear Craddock has been caught or has engaged with only Monmouth and Good Hope armoured ships against Scharnhorst and Gneisenau. Probably both British vessels sunk. Position of Canopus critical and fate of Glasgow and Otranto uncertain.

Proximity of concentrated German Squadron of 5 good ships will threaten gravely main trade route Rio to London. Essential recover control.

First Sea Lord requires Invincible and Inflexible for this purpose.

Sturdee goes Commander-in-Chief, South Atlantic and Pacific.

The two battlecruisers were relinquished and sailed to Devonport for supply and fitting out for the long journey south.

Churchill returned to his map and pieces to look at how von Spee’s position could change. If the Germans returned across the Pacific they would find a powerful Japanese squadron at Suva covering Australia and New Zealand which consisted of the battleship Kurama and two battleships as well as two light cruisers, the French light cruiser Montcalm and older protected Australian cruiser Encounter whilst another squadron was based in the Carolines. Coming down from North America the battlecruiser Australia, Japanese battleship Hizen, cruisers Idzumo and Newcastle. Around the Cape lay Stoddart with Canopus, Glasgow, and Bristol but they had been ordered not to engage until the battlecruisers arrived.

There was also a contingency plan with another force centred at the Cape of Good Hope centred around Defence (once relieved by the battlecruisers at Montevideo) and the pre-dreadnought Albion. The battlecruiser Princess Royal was dispatched to the Caribbean to work with the older armoured cruisers Berwick and Lancaster.

The noose was tightening.

As Churchill began moving ships around he telegraphed Captain Grant advising him to make for Montevideo and avoid action against a “superior force” and added;

If attacked, however, Admiralty is confident ship will in all circumstances be fought to the last as imperative to damage enemy whatever may be consequences.

Thoughts turned to the Falklands themselves and their precious coal supplies and port facilities and the Admiralty cabled the Governor;

German cruiser raid may take place. All Admiralty colliers should be concealed in unfrequented harbours. Be ready to destroy supplies useful to enemy and hide codes effectively on enemy ships being sighted.

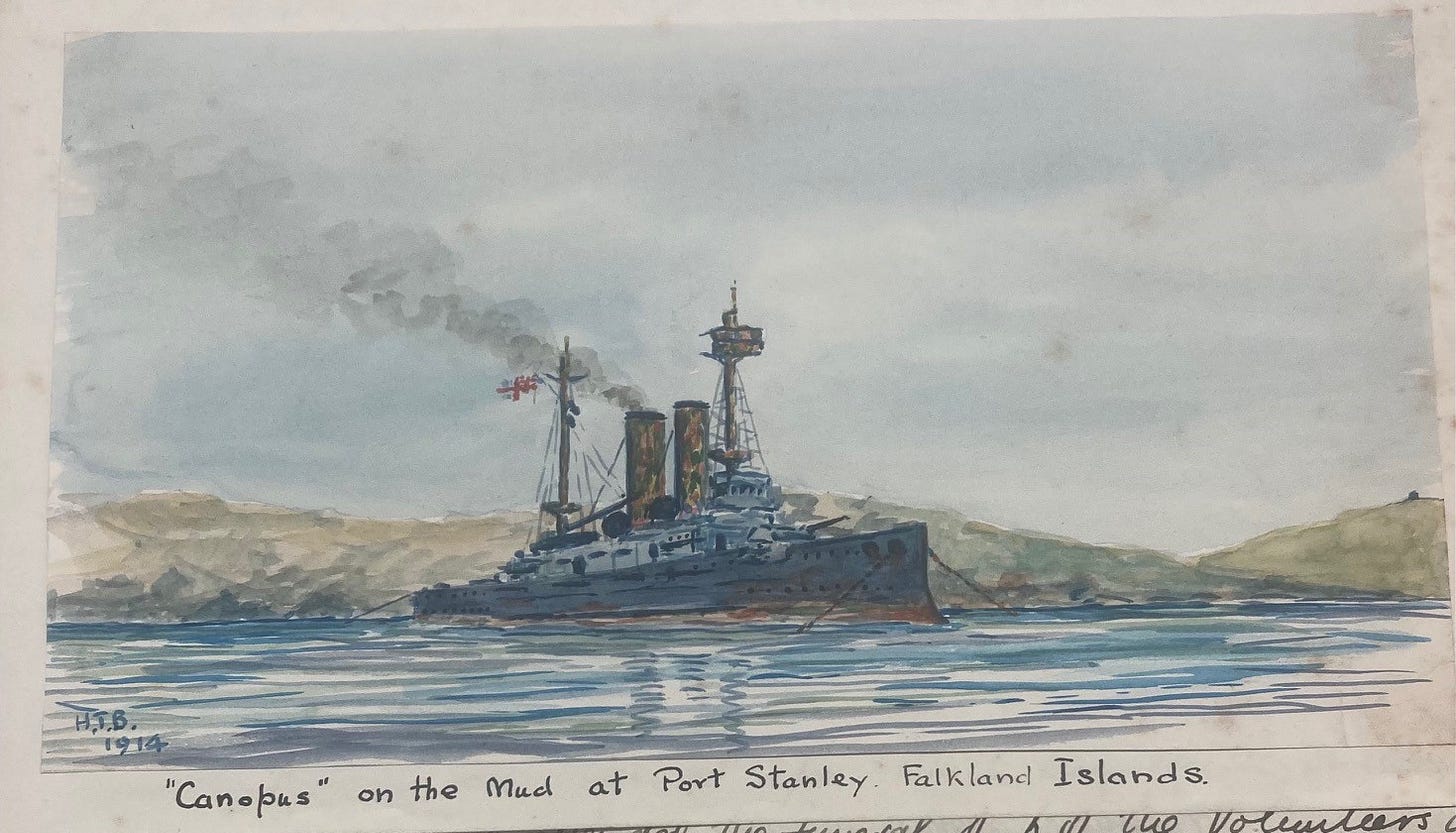

With Canopus still registering engine issues that too was sent to the Falklands with the following orders sent on the 9th November;

You are to remain in Stanley Harbour. Moor the ship so that the entrance is commanded by your guns. Extemporize mines outside entrance. Send down your top masts and be prepared for bombardment from outside the harbour. Stimulate the Governor to organize all local forces to make determined defence. Arrange observation stations on shore by which your fire on ships outside can be directed land guns or use boats’ torpedoes to sink a blocking ship to obtain a good berth.

Should Glasgow be able to get sufficient start of enemy to avoid capture, send her on to the River Plate; if not, moor her inside Canopus.

Repair your defects and wait orders.

These orders did bring a boost to morale with Captain Grant believing that Lord Fisher was expecting an attack on the Falklands and it gave Canopus the chance of “meeting the enemy and of effecting some damage on them in return for the destruction of our late squadron mates”

The battleship arrived at Port William at 4:30 p.m. and immediately began deploying lookouts on the island for the German attack that would come any day. The following day the Canopus redeployed to Stanley harbour where they had a better position for gunnery and a softer harbour bottom that would not damage the keel when she was grounded.

We have run her hard and fast on to the mud (on purpose) so it looks as if we were going to stay here till the end of the war - whenever that will be. Our poor dilapidated old engines have at last got a rest after tramping up and down the Atlantic and Pacific ocean for weeks on end with scarcely an interval. - Midshipman Philip de Carteret.

Grant began working his crew to setting up observation points, constructing extemporary mines, landing machine guns and situating them to cover obvious landing points as well as preparing gun mountings on land all in a South Westerly gale and driving snow.

I fully expected to have an alarming sick list from the shore parties, but was agreeably surprised to have next to none. It was chiefly, I think, to their all being seasoned men. The average on board was 36 years, not to mention the six grandfathers we had among the chief petty officers. - Captain H Grant

The gun mountings were bolted to heavy baulks of timber which were sunk into the ground and packed in with cement and then covered with stone and peat.

On the island a volunteer force of local men had been organised by the Governor numbering 160 who had been drilled by Captain Hobson RMLI and given a machine gun. The Governor had mounted fifty of the men as a reaction force should the Germans land somewhere more remote and had managed to scare up a field gun from somewhere. The Canopus’s eighty marines were also ready to be landed at a moment's notice to assist. On the 1st December eight of the volunteers were killed when the boat they were training in overturned, drowning them all possibly due to the temperature and possibly due to the thick seaweed. As it was a remote location they were not seen to capsize. Seven of the bodies were recovered and buried in Stanley Cemetery with grave markers for all eight.

I would mention that we received the greatest assistance from the Governor, the Falkland Island Company and the inhabitants of the colony, and if it had not been for their services in material, carpentering works etc., we should have fared badly, especially in the matter of huts for the men ashore etc. batteries, lighters for transporting guns and stores etc. - Captain Grant.

On the 25th November news arrived that the Scharnhorst had rounded Cape Horn on the 22nd and so could attack at any time so efforts were doubled to get the works completed.

On 26th November Grant reported to the Admiralty that he had deployed his guns thusly;

a.) Three 12 pounders at Ordinance Point covering the minefield and the harbour and the bay between York and Ordnance point.

b.) A 12 pounder at Hooker Point with a machine gun to defend the adjacent waters and landing area which the Germans would need to traverse if going to Port William or attacking the wireless station. This gun would also work with the Local defence force for this purpose.

c.) A 12 pounder was deployed at Arrow Point to cover the entrance of Port William harbour and could even cover Port Stanley’s. They also had a lookout station built there.

d.) Two 12 pounders were placed at Lake Point to repel landing forces at the sheltered Harriot bay

All of these batteries were linked by telephone as well as the observation point, Canopus, the lighthouse and the Wireless station. A field hospital was also established and fitted out with all of the ship’s spare stores, the Staff surgeon, Mr Wernet assisted by a junior surgeon and several Islanders including Dr Richard Wace. Other civilians, women and children, were evacuated from Stanley into the countryside so they would not be caught in any bombardment.

It was now a waiting game to see what would happen.

Back in London though pressure was being mounted on the departure time of the two battlecruisers as Devonport reported they could not get them ready before the 13th November. Churchill sent a very curt response;

Ships are to sail Wednesday 11th. They are needed for war service and dockyard arrangements must be made to conform. If necessary dockyard men should be sent away in the ships to return as opportunity may offer. You are held responsible for the speedy dispatch of these ships in a thoroughly efficient condition.

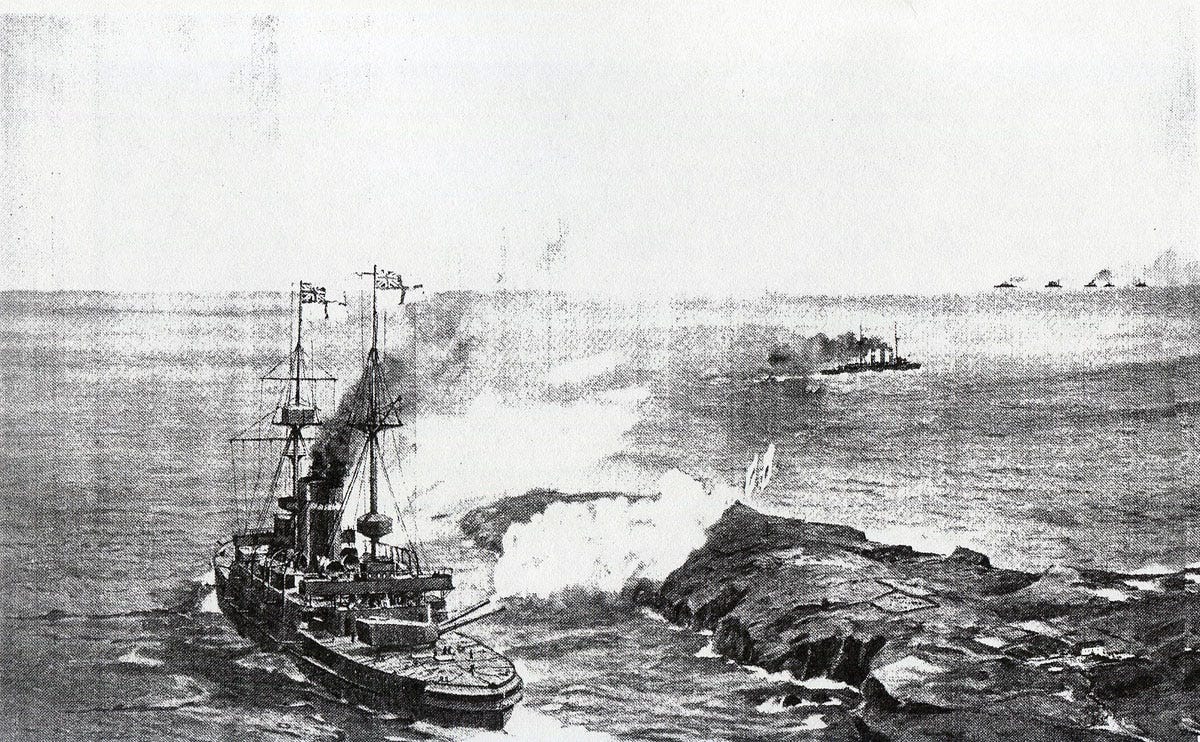

Needless to say the ships left on the 11th as planned and cruised at speed to Abrolhos where they joined Stoddart’s squadron and coaled on 26th November. With Defence dispatched to the Cape station, Sturdee proceeded with the armoured cruisers Cornwall, Kent and Carnarvon with the light cruisers Glasgow and Bristol and finally the auxiliary Orama. Travelling under wireless silence and out of sight of land the force arrived at Stanley on the 7th December in very cold awful weather with rain squalls.

Captain Grant reported to Sturdee immediately and gave him the full report of what he had managed to do to defend the island over the previous month much to the latter’s satisfaction who gave the Captain the position of senior Naval officer of the Port.

This included the coaling and provisioning arrangements of the squadron which had brought quite a small fleet of auxiliaries with them, amounting in all to eleven colliers and two supply ships. - Captain Grant.

Sturdee wanted the fleet to begin resupplying immediately and he was keen to press around the Cape and start hunting for von Spee’s ships and the slow process began immediately whist the Kent stood guarding the fleet.