Following the Battle of St Kitts and Nevis in January 1782 the position of the three opposing powers were looking very favourably on the Franco-Spanish fleet. The two allies had set about three priorities including supporting their Colonial American allies, capturing the Leeward islands and finally take Jamaica.

Although at St Kitts and Nevis Hood’s forces had acquitted themselves well against the Comte de Grasse’s forces they had been unable to relieve the French siege of the fort and both islands fell. Hood had to withdraw to St Lucia whilst the French withdrew to Martinique and everyone sat at an impasse. De Grasse decided that pushing to take all of the windward islands could be put down as a secondary objective as Jamaica was the jewel he wanted to pluck with its sugar trade which made up 20% of the British economy. On the 7th April 1782 de Grasse put to sea with thirty five ships of the line and a convoy of one hundred supply ships to meet with the Spanish force of twelve ships of the line and also to collect 15,000 soldiers at Saint Domingue.

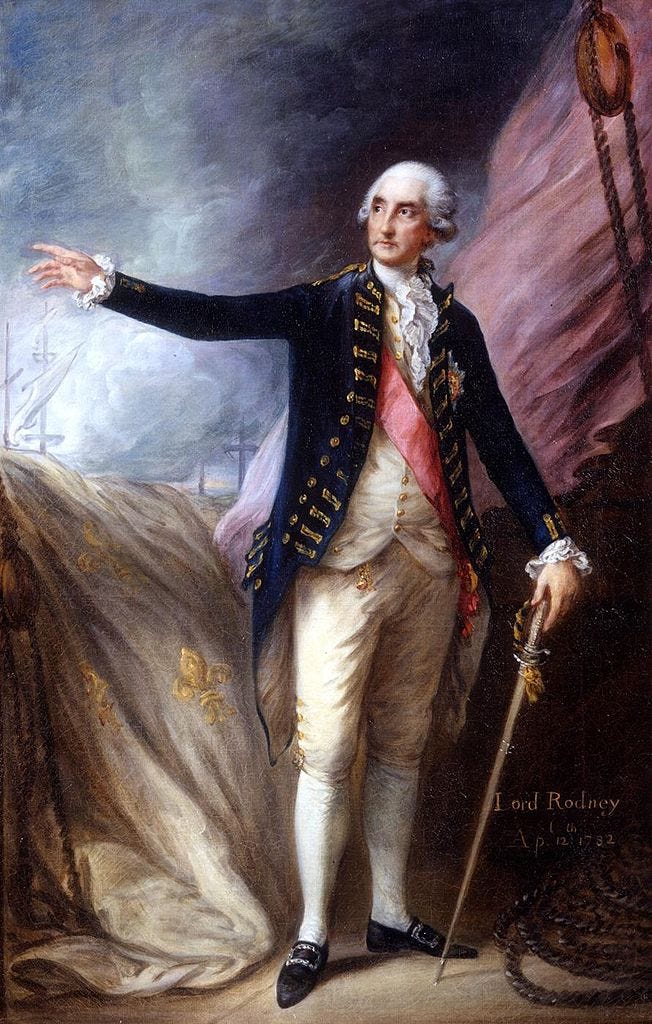

Hood’s superior, Admiral George Rodney, had returned from sick leave in Bath on 19th February off Barbados (meeting with Hood’s force on 25th at Antigua) and was adamant that defeating the French fleet at sea would end the threat. On learning of de Grasse’s sailing he put to sea on the 8th April and gave chase hoping to intercept them with the British fleet divided into three sections with Rodney commanding one (Admiral of the white aboard HMS Formidable) , Hood the second (Admiral of the red aboard HMS Barfleur) and Francis Samuel Drake the third (Admiral of the blue aboard HMS Princessa). The British force also had two advantages over the French in that they were armed with Cannonades on the upper decks which were flexible and great at close quarters and the ships had been sheathed in copper to cut down the marine growth fouling the hulls so that makes them move faster. Amongst the fleet was the Chatham built Namur under Captain Robert Fanshawe).

On the 9th April, the day after leaving St Lucia, Rodney’s force caught up to a very surprised de Grasse’s force. Immediately de Grasse ordered his warships to form line of battle to engage the British and to buy time for the convoy to withdraw to Guadeloupe and safety. At 8:30 a.m. de Grasse’s force stood to the south ready to escape to the east through the Dominica channel. Having only seen Hood’s squadron he was hoping to use his superior numbers to defeat him and then continue the Jamaica plan.

From 9:30 a.m. Hood’s force came under long range fire from the French van (under Vice Admiral Louis-Phillipe Rigaud) and although there was little damage the French guns had got the measure of Hood’s force. Rodney and Drake had lost the wind and were becalmed to the lee of Dominica. This changed at 11:30 a.m. with Rodney’s flagship, Formidable supported by Namur and Duke. arriving and joining the counter firing but it would not be until 1:45 p.m. before the rest of the fleet could arrive and de Grasse would need to commit the rest of his force, something the French Admiral was disinclined to do.

By 6:00 p.m. the French supply ships were finally clear of the fleet and de Grasse withdrew with them leaving Hood’s squadron to lick its wounds as the rest of the British could arrive. Although Hood had suffered losses including Captain Bayne of the Alfred (who had lost both legs to chain shot) , the Monatagu and Royal Oak were both damaged de Grasse had missed a golden opportunity. Granted he would have suffered damage and losses but had he engaged Hood’s squadron with his full force he could have decimated the British force which would have hobbled Rodney’s operations. As it was the Caton suffered the most with a gun explosion which killed eighty of her crew and saw her withdraw from the action to the Saintes islands.

As night set in Rodney set about preparing the next day’s action by reordering the squadrons and putting Hood’s damaged force in the rear and bringing Drake up to the van.

The next day, 10th April, saw the French moving along its previous course with absolutely no interest in turning to attack Rodney which the British Admiral believed they would. There was some confusion over the amount of sail to be deployed and Drake had to detach a Frigate to return to Rodney to get confirmation. By the end of the day the French were some 16 miles away.

That night Fleet Captain Sir Charles Douglas ordered the Fleet to shorten sail allowing the French to gain more distance on Rodney.

By the morning of the 11th the French were off an archipelago in the channel between Guadeloupe and Dominica with Drake still in pursuit but the French were gaining more distance and the chase was looking fruitless.

However fate intervened with the Zele colliding with the Jason causing the latter to withdraw to Basse-terre at St Kits and Charles-Rene de Gras-Previllle’s ship falling behind the main French force under the protection of the Maganime. Rodney believed that if they were attacked de Grasse would have to sail back to rescue them but despite manoeuvres they weren’t attacked on the 11th.

As the sun rose on the 12th April the French were between six and twelve miles away in a scattered formation and in the Northern end of the Saintes passage. The Zele had had another collision in the night and hit the flagship, Ville de Paris and was now under tow back to Guadeloupe by the frigate Astree. The Ville de Paris was standing eight miles from the British force between the Zele and the rest of their force.

Early in the morning Hood’s Monarch, Valiant, Centaur and Belliqueux were sent to to overtake the wounded Zele and it sparked the reaction Rodney hoped for with Ville de Paris signalling the rest of the fleet to close on her position whilst de Grasse moved to dissuade the pursuing British ships. This was more than a bit problematic as the whole force had to turn and manoeuvre in the tight confines of the Straits and although there were no more collisions the order of the already scattered vessels became more chaotic especially in the morning fog.

For Rodney it was a question of whether or not the French would commit a full engagement or turn and fire a few broadsides to attempt to ward the British off. How much was one damaged 76 gun ship worth?

With a shift in the wind it looked like the British would be unable to engage effectively and that all action would consist of a passing cannonade at best. Rodney passed the order;

Engage the enemy more closely.

The leadership in the British line, HMS Marlborough (Captain Taylor Penny) was able to haul North-north-east and was opposite the ninth French ship, Brave, and was able to open fire at 7:57 a.m. which was the first shots of the line and the battle. By 8:30 a.m the first eighteen British ships in the line were engaging the French centre and rear. The damage caused by the new cannonades was quite impressive with the French Glorieux (just to the aft of Ville de Paris), which had already been damaged by the Duke, found herself under the guns of the Formidable. Despite white colours nailed to the mast and a Sergeant waving a white flag from his halberd from the foredeck the Formidable proceeded in a ten minute bombardment that left the already damaged French vessel completely shattered and dismasted.

Both sides were aiming for rigging and sails though the Prince George suffered nine killed and twenty four wounded. As the dead were thrown overboard to clear the gun decks sharks were seen in the water taking the bodies and any unfortunate living crewman who was blown overboard.

There was also another problem for the French which was another issue of war, when subordinates do not understand the orders of the fleet commander and, in this period being unable to question the orders effectively, only half-heartedly carry them out. De Grasse ordered Vice-Admiral the Comte de Bougainville to bring the French van, hitherto unengaged, to strike the British rear but de Bougainville didn’t understand why he was being sent into an area of low wind (caused by the proximity of Dominica).

The British van passed by the French rear and some of the vessels hoved too to repair damage but Captain Saumarez on the Russell brought his ship around and charged back into the action.

The French line was also turning to pass in the opposite direction meaning the French would be back on their original course and leaving the British in their wake, something Rodney was not keen to let happen. As Formidable passed the shattered Glorieux where a large gap in the French line had formed Rodney was persuaded by Captain Douglas to turn into the gap, cut the French line and take the weather gauge.

The British flagship led the Namur, St Albans, Canada, Repulse and Ajax with all of the ships putting fire into the Glorieux and Diademe either side of their advance. Other British ships also turned to cut the line where they were with the Duke passing between the Magnanime and Refiechi but found herself cut off and under fire from the two French ships as well as the supporting Diademe and Reflechi and, according to French sources post battle, surrendered to Vice Admiral de Vaundreuil’s Triomphant but the Formidable and Namur moved up to support the French ships at point blank range.

Another gap was exploited by Commodore Affleck aboard the Bedford which cut between the Cesar and Dauphin Royal and this gap was quickly further exploited by Hood’s thirteen ships firing heavily into the two French ships and the Hector.

The French situation was getting dire and de Grasse upon realising the Glorieux’s condition was forced to act and he brought Ville de Paris up to support her and a frigate, the former HMS Richmond now renamed Richemont, to tow the ship away. This brave attempt was carried out by Denis Decres, of the Richemont, who attempted to row across and attach a tow to the shattered Glorieux but as the British fire intensified the surviving First Lieutenant, De Kerlessi, aboard Glorieux’s deck cut the tow to save Richemont from the same fate as his already shattered ship.

One of the stories from the battle was that of Captain Henry Savage of the Hercules who suffered from gout and usually sat on the quarter deck in a chair but through the Saintes he was instead propped up and shouting insults at the French through a speaking trumpet and shaking his fists at each passing French vessel. Even after being wounded and taken away below deck he managed to get back to the deck and resume his personal tirade against the enemy.

The battle dissolved into thick gunpowder smoke and visibility became pretty much nil until a wind at 1:00 p.m. blew the smoke clear showing the full situation facing de Grasse. De Bougainville’s van was two miles windward of de Grasse and de Vaundreuil’s rear echelon was was four miles leeward. The damaged Cesar, Hector and Glorieux were in exposed positions with the first and second between the French van and British and the third windward of the Ville de Paris. De Grasse ordered the fleet to reform the line so that they could cut off Hood’s force but his van let him down with de Bougainville carrying out halfhearted moves from only one ship, Souverain.

Rodney’s force was able to reform a lot more efficiently and made moves to deal with any isolated French ships. Hood had boats lowered to tow Barfleur into position to be able to chase the French but to his surprise saw the Formidable still flying “close for action”. Hood then ordered his vessels to chase at 2 p.m. with some of Rodney’s echelon joining him.

The shattered Glorieux surrendered to the Royal Oak and the Bedford and Centaur caught and forced Cesar to surrender. William Cornwallis’ Canada closed in with the Hector and her devastating fire caused the French crew to flee for cover before Captain Claude Eugene Chauchouat de la Vicomte rallied them to a brave résistance. The Alcide approached to assist the Canada and the Hector eventually surrendered, her Captain dead and six feet of water flowing through hull impact hulls at 6:20 p.m.

Canada, Monarch, Marlborough and Russell then isolated the Ville de Paris which had had its main rigging blasted away and rudder disabled. To make matters worse for de Grasse, the Barfleur approached and began mercilessly bombarding the flagship. With three hundred men dead and only a couple of people still uninjured on the upper decks de Grasse personally struck the colours of his flagship and surrendered his sword to Rodney’s favourite, Lord Cranstoun, when men from Formidable boarded.

With the sun coming down and Rodney called off the pursuit and the British had maintained a disciplined approach to the battle where as de Grasse was let down by his subordinates, though King Louis would hold him responsible for the defeat and banish him from Court. Tragedy struck that evening when fifty nine men of a British Prize crew locked the Cesar’s crew below deck and took control of the vessel. One of the French crew accidentally set fire to a barrel of alcohol whilst breaking into the officer’s liquor store. The resulting fire reached the magazine and the ship exploded killing four hundred French crew including her Captain and fifty of the British prize crew. As the fire spread men were jumping overboard to escape and straight into the jaws of waiting sharks.

The Bedford attempted to pursue the French force, having not seen Rodney’s signal to halt action but the real pursuit did not occur until the 17th April following a period of repair and refit in becalmed waters. Hood’s vessels managed to catch up with five stragglers on the 18th in the Mona passage. The Belliqueux crossed shoals so shallow that the keel was passing through soft sand with the Valiant coming up with her to take the Caton, Ceres and the Amiable.

So why is the Battle of Saintes so important?

Well, arguably it was where Nelson would get the idea of cutting the line came from but I’m going to be honest I don’t know enough about the period to say for certain. The French Court were not happy with the “Grim disaster” as Marquis de Castries, the Navy minister, described it. Fresh taxes were levied to help raise money for new ships as the French navy lost fifteen ships in April of that year, five at the Saintes. It could have been a lot worse with Hood arguing that Rodney could have captured up to twenty ships had he pursued them with Cornwallis quietly in agreement. Rodney and Hood were raised to the peerage by a grateful King George and the Comte de Grasse presented to him.

The French fleet managed to get to Martinique but were soon struck by disease which ravaged the army that was ready for the Jamaica invasion and thousands died which saw the invasion abandoned and the Franco-Spanish decided to defend the territories they had gained instead.

The victory also gave the British impetus in the peace negotiations with the Colonies and the French & Spanish especially when Admiral Richard Howe relieved the beleaguered Gibraltar garrison. They were less inclined to give in to demands such as Newfoundland and Canada from the Colonials or Gibraltar to the Spanish.

Although not quite a complete victory it was powerful enough to have a massive effect on the world stage.

In my mock O Level I surmised that Nelson had learnt about breaking the line from Rodney and earned the wrath of my history teacher for drifting into the realms of historical fiction in the absence of evidential sources. Ouch but life lesson learnt by the 15 year old me.

Great. Just read about this last night. For my sins I hadn’t really known about it and wanted to learn more. Thanks for my new evening reading!