Catastrophe

The loss of Prince of Wales and Repulse

Admiral Tom Phillips was about to make a mistake, a pretty major mistake which would completely destroy Force Z and cost him and 879 officers and men of the Royal Navy their lives.

With the growing of Japanese aggression within the region the British upper echelons decided something needed to be done to cause a deterrent or at least form a nucleus of a taskforce in the region.

If you caught my Pearl Harbor post then you’ll know what a military and political quagmire Japan had got themselves into with their war in China and their aims of setting up a Co-prosperity sphere (Empire) within the Pacific region. Whilst America and her warships would be the main threat to their proposed expansion there was also concern about what Britain might do as well as a look at British territories in China, Malaya and Burma, what they could offer the Empire and their strategic importance. Burma had the only other route into China by road and saw Western supplies for the Chinese Nationalists being delivered along it. Singapore and Malaya held a strategic point on the map and a main shipping lane. More importantly, Britain was at war with Japan’s ally, Germany, and distracted.

The War in Europe was not going well at the end of t1941 with the Germans storming through Libya and Egypt, the Mediterranean Sea under Axis control, Europe under the jackboot, Moscow under threat by Panzer columns and Britain, her Empire and a hotch potch of Free nations forces that had escaped Europe, fighting on alone. They w ere weak and could be defeated and more importantly following the cruise of the German raider Atlantis, the Japanese had the defensive plans and a review of Burma and Malaya as well as Naval and RAF strengths.

The main defence of Singapore and Malaya was the fortress of Singapore itself. The British had invested large amounts of money and resources into fortifying the port and had been very successful - it was a hard nut to crack if you were to attack from the seaward side. The Army also thought up Operation Matador to try and engage the Japanese invasion before it really got going but with the back up plan that they could always fall back to the Singapore fortress. The Far East was very much the bottom of the resource list at this point with the lion’s share of anything staying in the Home islands, then what was left went to Africa and the Mediterranean and then literally anything else went to the Far East or squadrons were rotated out from Egypt to rest and recuperate.

Several meetings were held in London by the British Defence Committee during the period that covered the fall of the Konoe government in Tokyo and its replacement with a more aggressive one under Hideki Tojo (taking charge on 18 October). In the meeting on the 20 October the final decision was made to dispatch a force of battleships as a deterrent to Japanese aggression, ignoring the fact that Japan had a whole fleet at its disposal.

Sir Dudley Pound said that what was needed was a whole force of capital ships, pretty much the lion’s share of the existing surface fleet, which was obviously not possible with the other two Axis navies to deal with. Churchill felt that two would be enough with an aircraft carrier in support.

For me this makes no tactical sense. The Japanese had a whole fleet including several modern heavy cruisers and battleships as well as the crucial aircraft carriers. One Battleship and a battle-cruiser were not going to be able to stem the tide and it would have been better to dispatch a whole taskforce - though this would have been futile and seen further losses, losses the Royal Navy could not afford with the on going war in Europe and North Africa. I guess they could not do nothing but… Maybe I’m writing with hindsight.

When they consulted the roster of available battleships one choice became obvious. The Nelson had taken a torpedo in September and was not repaired yet, Rodney’s crew were on leave, the Revenge class battleships were old and had some severe issues with one sailor remembering post war that the drinking water always tasted of rust on board and that his was in a bad way.

The final proposal was for the only available battleship in the Mediterranean, the Prince of Wales, which was still a very new battleship having only been commissioned in January and not completed until March that year. Admiral Tovey felt that she would not be suited as she had no airconditioning aboard, the heat and humidity would negatively effect her. She would be accompanied by the Renown class battle-cruiser Repulse and the carrier Indomitable until the latter ran aground and had to under go repairs. The Hermes was ordered to go out in her place but she would be delayed in doing so. There was a hope that the American fleet would move up to Singapore to assist against the Japanese threat but Pearl Harbor would stop this.

The Prince of Wales was sent round the long way via Cape Town which would give the government time to reconsider the move but when she arrived at Cape Town she was greenlit to carry on. Force G consisting of Prince of Wales, Repulse and destroyers Encounter, Electra, Express and Jupiter arriving at Singapore on 2nd December. The older Danae class cruisers Durban, Danae and Dragon as well as the Mauritius were also in port but due to their age were not much use to Admiral Tom Phillips.

To make matters worse the Japanese knew they were coming. As part of the deterrent Churchill had announced on radio that the Prince of Wales and Repulse were on their way so the Japanese reacted accordingly. Fresh bombers were sent to reinforce the Kanoya and Genzan air groups and both groups began training for anti-shipping torpedo attacks.

The balloon went up on 8 December with attacks on Malaya and air raids on Singapore with the capital ships adding their guns to the anti-aircraft barrage though it was found the heat was beginning to affect the ammunition somewhat detrimentally.

News of Pearl Harbor arrived, the US Navy’s inability to send capital units to reinforce Phillips and that the Japanese began invading the peninsula. It was decided that the renamed Force Z was not strong enough to repel the Japanese forces alone but under pressure Phillips decided on an offensive sweep to try and intercept and destroy a Japanese landing force.

However there were two problems. Firstly there was no air support available. The RAF had taken quite a pounding with their bases being hit first and with their priorities being to protect the airfields, their bombers and Singapore with already stretched resources. The official history for the RAF in the Far East is very clear; they had warned Phillips that there was not necessarily going to be air support but they would try and keep a squadron of Buffalo, (RAAF 453 Squadron) available on request.

Phillips did not rate airpower though. He firmly believed that aircaft could be seen off with the stiff resolve of a Commander and steady fire.

There are two trains of thought within naval theorists post World War One with the big gun proponents believing that naval battles will be fought and one the way they always had - with battleships with large guns whilst others looked at the growth of airpower. By the Second World War there was still no evidence of aircraft being able to dominate larger warships. Operation Halberd in September 1941 saw repeated Italian air attacks on a convoy heading to Malta and sank none of the escorts and only one of the convoy’s ships. Yes, the Nelson had taken a solitary torpedo and lost speed but she was still afloat. The biggest concern would be submarines.

The other issue was that the squadron would be moving without aerial reconnaissance or knowledge of Japanese positions. There was a belief that originally they would be able to read the Japanese radio decrypts but this hadn’t happened by the time the War started.

Ultimately, Phillips was taking his squadron out into the unknown to find an unknown number of enemies with an unknown number of aircraft and with little ability to deal with them.

I personally believe that Phillips should have thought of the long game and the lives of his crew and withdrawn from the region back to Colombo with his two larger ships forming the nucleus of a new force to retake the region, preferably with the Hermes providing an air component. There was no way that this would have happened though as this move would have been career ending and Phillips had already written off the danger of enemy aircraft. If the Germans and Italians couldn’t sink one of their vessels then the Japanese would certainly not be able to with a common belief that Japanese aircraft were probably First World War vintage and made from rice paper and bamboo. More pointedly the RAF had not been able to sink the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau in the confines of Brest harbour where they could not move so what hope did the Japanese have against ships that could move out of the way?

On top of that the Prince of Wales had High Angle Control System (HACS) a long range radar directed guns which had proved effective during Halberd.

Phillips was also only in the Far East as he had disagreed with Churchill publicly and so had been promoted and sent away without the combat experience you would need to carry out an independent War command.

General Jan Smuts had a similar position to me but also argued that the Fleet should scatter and act independently attacking the enemy at times of opportunities and gaining supplies from tankers and ships able to get to their secluded hiding spots. This wouldn’t have worked as demonstrated by von Spee when he was in the same position back in 1914. You cannot guarantee supply and the Japanese fleet (with their air cover) would soon find them.

Nevertheless the Force consisting of the Prince of Wales, Repulse, destroyers Electra, Express, Vampire and Tenedos set sail ot 5:15 p.m. on the 8 December to intercept a Japanese convoy they thought they would be able to intercept off Singora on 10 December.

The Japanese were aware of the British warships in Singapore and also that they had been undamaged by their air raids. They also appraised that the British would soon be heading to attack Japanese landings but they did not think it would take long before they did intervene. They must attack them imminently. Before the bombers could take off the mission was scrubbed as a fresh reconnaissance report came in that the harbour was empty and with the onset of night time they would have to wait and see what the state of play would be in the morning.

Phillips had been mulling over the situation through the night and sent this signal to all ships on the morning of 9th December:

The enemy has made several landings on the north coast of Malaya and has made local progress, our army is not large and is hard pressed in places. Our air force has had to destroy and abandon one or more aerodromes. Meanwhile fast transports lie off the coast.

This is our opportunity before the enemy can establish himself. We have made a wide circuit to avoid air reconnaissance and hope to surprise the enemy shortly after sunrise to-morrow, Wednesday. We may have the luck to try our metal against the old Japanese battle cruiser Kongo or against some Japanese cruisers and destroyers which are reported in the Gulf of Siam. We are sure to get some useful practice with the HA armament.

Whatever we meet I want to finish quickly and so get well clear to the eastward before the Japanese can mass too formidable a scale of an attack against us. So shoot to sink. - Admiral Tom Phillips

Things were looking up for Force Z as the weather was awful with low cloud and rain making spotting by aircraft very difficult. IF this weather could continue all day then they would be fine to attack the next day and with the heavy calibre guns they would soon decimate the predicted Japanese escorts. They would come a hell for leather then rush back to base with Japanese aircraft chasing them.

By lunch time they had only sighted two aircraft, well one a lookout thought he had seen which remained unidentified through the rain clouds and a RAF Catalina was definitely sighted. It looked like they were going to get away with it. Even better news came through that the Japanese were landing at Singora and that in eighteen hours, when Force Z arrived, they would catch the transports as they prepared to leave. By 4:30 p.m. they were 170 miles away from the target area and all they had to do was turn to 80 degrees and head through the night so that when the sun came up the Japanese force would see the British ships waiting for them.

What they didn’t know was the Japanese did know exactly where they were as at around 2:00 p.m. the submarine I-65 had spotted them and had been following ever since and would do until 7 p.m.

Also at 5:30 p.m. the weather cleared and the mist lifted and suddenly the lookouts were aware of Japanese spotter aircraft, out of range, but up in the blue sky watching and reporting back.

News reached the 22nd Air flotilla’s Bombers catching them mid bombing-up for a standard air raid on Singapore. The bombs were removed and torpedoes loaded instead though they were not ready until 6 p.m. as night began to fall. They did take off to carry out a night raid on the British ships but bad weather and poor visibility meant they were unable to find them and eventually gave up and returned to base around midnight.

The Japanese 2nd Fleet consisting of the battleship Kongo, Haruna, three of the Takao heavy cruisers and eight destroyers were dispatched to join the 7th cruiser division (the four Mogami class heavy cruisers, a light cruiser and four destroyers) to swing south and search for the British too.

Phillips knew none of this and continued to head for the target area minus Tenedos which had run short of fuel and was returning to Singapore. However he was starting to believe that his best shield, surprise, was ebbing away. Up until 7:00 p.m.the force continued north then turned northwest with an increase of speed as if rushing for the coast knowing full well that the Japanese aircraft were still watching them. At 8 p.m. the force were signalled to turn south and reduce speed to conserve fuel in the destroyers, the mission was cancelled and it was hoped that any information garnered by the Aichi floatplanes would point the Japanese in the wrong direction.

However, during the night the two fleets got within five miles of each other without anyone sighting the other fleet and the Prince of Wales’ radar not detecting any ships. What gave it all away was a flare dropped by a Japanese aircraft over Vice-Admiral Ozawa’s flagship, Chokai, which had been operating independently and had been misidentified. Both forces saw the flare and whilst the Japanese turned north-east away from it Phillips, his concerns that the element of surprise had been lost, continued away to the southeast.

A report from Singapore informed Phillips that a Japanese force was landing at Kuantan halfway between Singapore and his original landing space of Kota Bharu and so at 12:50 a.m. Phillips, again changed his plan and headed for the new target area.

They were still not safe though as unknown to them they had been spotted and attacked by the submarine I-58 at around three in the morning. Following all five torpedoes missing the ships the Japanese submarine followed them until around 6:00 a.m. reporting their position. Ten bombers took off at 6:00 a.m. to carryout a reconnaissance in force with others taking off at 7:55 a.m., 8:14 a.m. and 8:20 a.m. with orders to head to the most likely position of the British ships and see what they could find.

The British arrived off Kuantan first thing in the morning but there was nothing there. The Prince of Wales launched their Walrus aircraft which flew over the area and confirmed there were no Japanese vessels present before turning for Singapore. The Express also checked the area but found nothing and again the force began turning south for Singapore.

At around 10:00 a.m. the destroyer Tenedos, some 140 miles to the south still sailing for Singapore, reported that she was under attack by Japanese bombers. The G3M bombers mis-identified the destroyer as a battleship and began dropping their armour piercing bombs on the smaller ship which managed to avoid any damage.

The Japanese aircraft were searching much further south having worked out that if the British force was withdrawing south all night then they would be in that position unknowing that Phillips had taken a detour. This would be useful for Phillips because the Japanese were searching in the wrong place and by the time they reached that position hopefully the Japanese would have left the area.

Unfortunately for Phillips and the rest of Force Z, Ensign Masato Hoashi’s scout aircraft was out of position and to the north of the attack on Tenedos and at 10:15 a.m. he reported the Prince of Wales and Repulse. The swarm of Japanese aircraft, although low on fuel, immediately began vectoring to their position.

Aboard the British ships the men had stepped down from action stations and were washing, resting, grabbing a bit of food.

When all of a sudden, the warning system on the ship - “Aircraft approaching” - Action stations. So off I went, climbing up the mast. Looking through my binoculars now, glinting like little fireflies at about at 17,000 feet were nine little silver shining aeroplanes. - John Gaynor © IWM 8246

As the attack was a little rushed the Japanese aircraft attacked in waves as they arrived rather than in a massed attack with the first wave of eight (rather than the nine John Gaynor thought he saw) from the Mihoro air corps coming in at 11:13 a.m.

The Prince of Wales anti-aircraft guns opened up on the descending Nell’s to no avail. John Gaynor watched on helplessly as they released their bombs and they began to descend. Most missed the target but one did strike the Walrus hanger and penetrated through to the Marine’s mess area.

There was a terrific thunder and the ship shuddered. These bombs, some of the bombs hit the ship about amidships and the whole ship sort of jumped… A lot of our lookouts happened to be Liverpool men, they had been schooled, they had been trained that when you are being attacked the forms of attack from the air are high level bombing, which this was, dive-bombing, which this wasn’t and torpedo bombing, which this wasn’t. So all of the lookouts who had all these binoculars and nothing else to do but one hour in every four to look for aeroplanes - they were all at Hendon air days and they were all gazing up at the bombers. All of a sudden zooming across the water there were seven or eight torpedo bombers coming straight for HMS Prince of Wales.

We’d been firing up in the air and by the time we managed to depress our sights and get ready for the change in circumstances, which was the torpedo bombers were more dangerous, they’d let go of their torpedoes and the torpedoes were homing in on the ship. John Gaynor © 8246

The seventeen torpedo bombers came in at 11:40 splitting into two groups with eight attacking Repulse and the rest on Prince of Wales. Only one torpedo hit the battleship;

I think one or two hit the ship and pushed the ship sideways. The ship weighed about 35,000 tons but the torpedoes pushed the ship and she actually jumped. - John Gaynor.

Despite shooting down one of the attacking bombers the Prince of Wales had taken a hit to the point where the port propeller shaft left the hull and the motion of the propeller tore the shaft away causing her to lose speed (down to 16 knots) and take on 2400 tons of water. Engine Room B was flooded and evacuated as was the Central auxiliary machine room, Y Boiler Room and several aft compartments. The in rush of water also caused her to list to port by 11.5 degrees whilst the loss of the boiler room led to power being lost to the vital 5.25” gun turrets which were providing most of the effective anti-aircraft fire, also a lot of the auxiliary systems, like internal communications, lost power and more vitally, the pumps, electric steering and the mounts for the 2 pounder guns which now had to be moved manually. That one torpedo strike had killed the battleship.

At 12:20 twenty six bombers of the Kanoya Air Group arrived and attacked. Three torpedoes struck the Prince of Wales, one at the bow, one by B turret and one near Y turret. Counter flooding was ordered to try and bring the anti-aircraft guns back into the fray as the list has put them too high (or too low depending on which side the attack comes from) and small arms are grabbed by desperate crew to provide any sort of fire.

Captain Tennant on Repulse was not having a better time of it. They had already been straddled by two bombs (which missed) and struck by a third which penetrated their Walrus hanger and the armoured deck below starting a fire. Damage control teams pushed the aircraft into the sea and fought the flames before they became an inferno. Despite the smoke and casualties the vessel had suffered no critical damage and she steamed on.

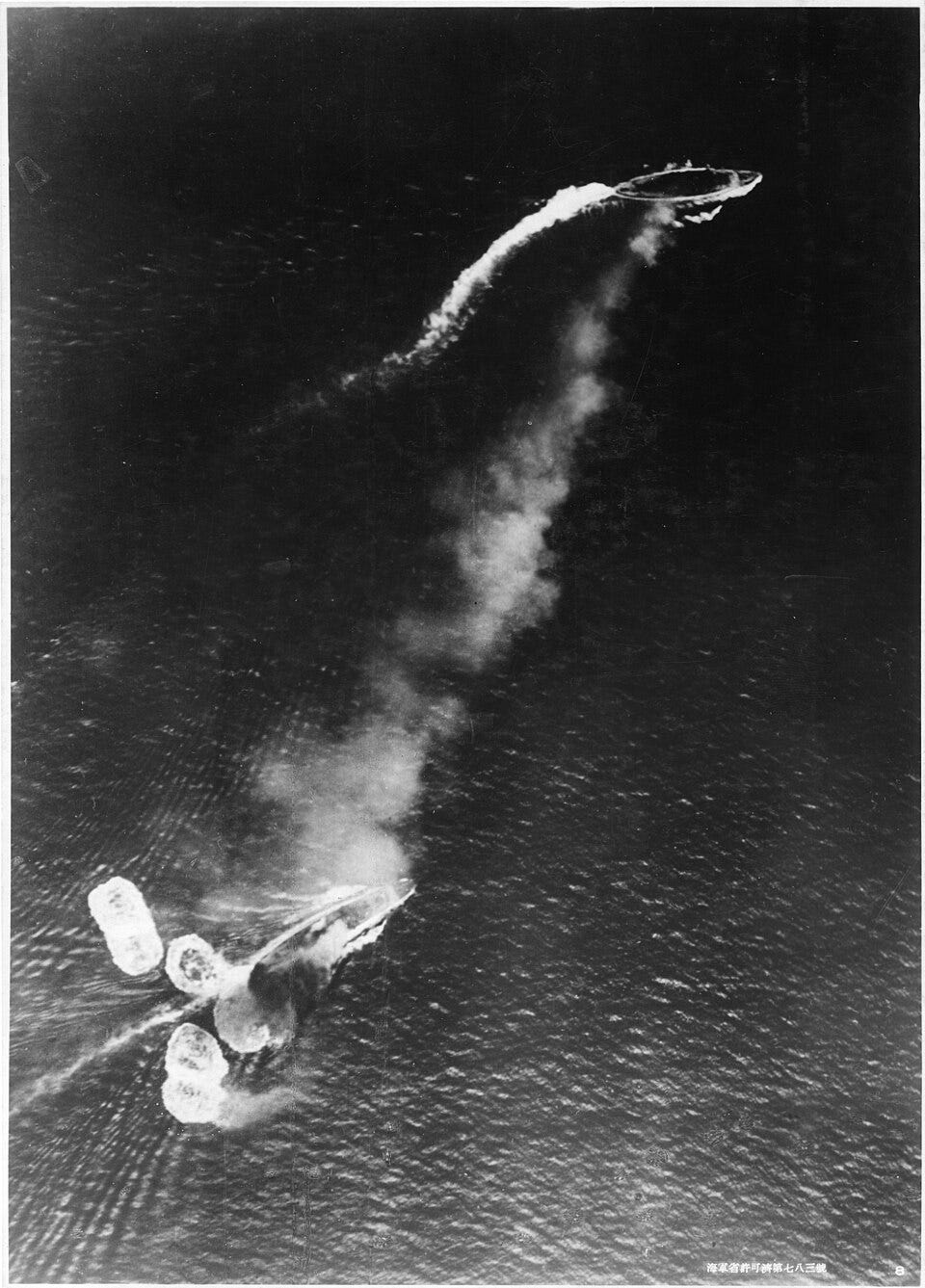

Tennant treated the Repulse like a cruiser or destroyer and at full speed began manoeuvring to avoid the torpedoes. As the lookouts spot the aircraft coming in and the torpedoes hitting the water the helm is turned over. In all she is missed by a staggering 19 torpedoes that were coming in from either attacking aircraft or ones that had missed Prince of Wales all thanks to these vigorous manoeuvres. As the bombers came in at 12,000 feet the Repulse again began dodging to avoid damage and managed to come out unscathed again!

Her luck ran out at 12:23 p.m. when twenty Japanese bombers attack from multiple vectors despite the 15” shells firing into the sea directly in front of the bombers to try and knock them out of the air. Eight torpedoes are dropped on her starboard side and Tennant orders her hard over to “comb” the torpedoes but tragically three more aircraft drop theirs off to her portside. There was nothing they could do to avoid this new incoming threat.

Everyone braced for impact but the first strike does little damage to the battle-cruiser and she still continues on at 25 knots! The second torpedo strikes her and knocks out her rudder, locking her in a circular course.

Three more bombers attack, dropping their torpedoes and overflying the Repulse strafing the decks with their forward machine guns. John Gaynor witnessed what happened next;

She was just firing at a torpedo bomber and luckily she hit the torpedo bomber, the torpedo exploded and the plane and its contents went up in a lovely cloud of orange smoke and I thought how marvelous. Then the poor old Repulse caught a torpedo as she was heeling over as she was turning. It helped her to heel over and she went over just like that. - John Gaynor

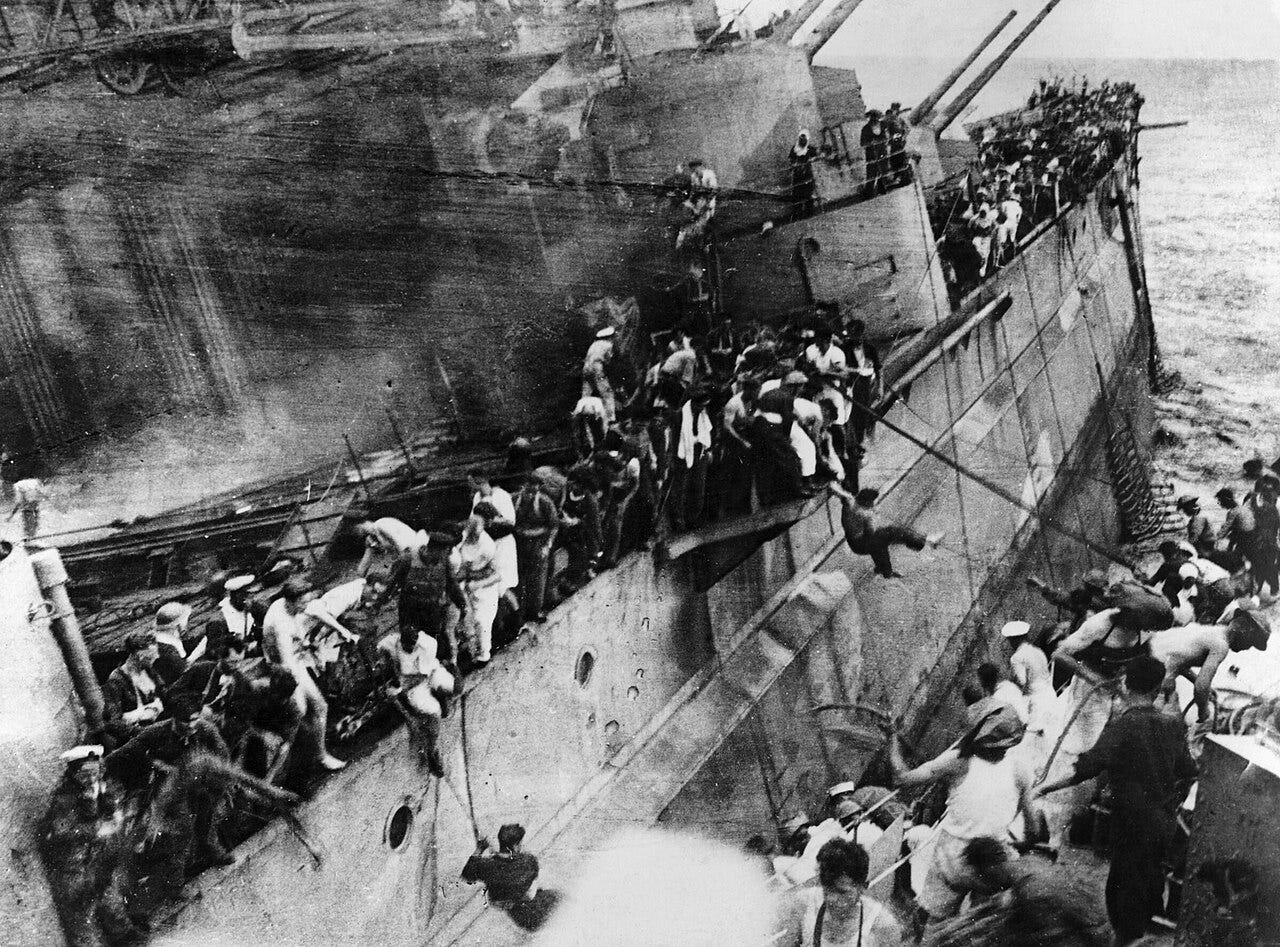

The second hit her hard and as she was off her centre of gravity she rolled over and capsized pretty much immediately. As she was rolling over another six torpedoes were dropped with one impacting the already doomed ship. As the Repulse entered her death throes the destroyers began to come in to rescue survivors.

The Prince of Wales had taken on around 18,000 tons of water by 12:51 p.m.when she was hit by a 500kg bomb from high level.

The Express came alongside and gang planks and ropes thrown across despite the widening gap caused by the list to port. Many men were lost between the two ships in these conditions and when cables between them snapped. At the last minute the Express pulled away but suffers a 20 foot long gash in her side from colliding with the Prince of Wales’ hull as she capsized.

The battle was over.

HMS Prince of Wales sunk… HMS Electra’s signal to Singapore.

The last cruise of Force Z had cost the Royal Navy a battleship, a battle-cruiser and 879 Officers and Men including Tom Phillips and Captain Leach of Prince of Wales. Captain Tennant survived.

The Japanese lost four aircraft with 28 damaged - a total of eighteen men killed. Air power, at least in the Pacific theatre, was proving to trump sea power.